Archives of architecture - Interview #5 at the Canadian Centre for Architecture

Article in English

Gathered for the first time to collectively respond to an interview, four of the associate directors of the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA) in Montreal, share their experiences in dealing with the challenges in promoting contemporary building culture.

espazium.ch: CCA owns nearly 200 archives of renowned architects. What are your criteria for acquiring new fonds and how have they evolved over time?

Martien de Vletter: The CCA Collection is a tool for investigating and generating ideas in and on architecture, ideas that support contemporary debate and often unravel the process of architecture, which is our specific lens for approaching the world. The leading criterion over the years has always been relevance for contemporary and future research, by us and by others—and of course, we’re not always able to understand relevance and potential in the moment, and we must constantly reframe our own thinking. But generally, we feel a responsibility to bring together possible sets of topics and figures who have had a global influence on architecture throughout history.

Often ideas of architecture and the city are related to or traceable in the archive of an individual or a practice. This is why the CCA has focused on archives since its start. But archives also contain the work of an entire career through time, and through many projects. We are always looking for opportunities to see and reinterpret the collection from these two perspectives, topically and transversally.

We have developed a layered acquisition strategy, where in certain cases we actively reach out to architects to ask to donate all material that has been produced around one project (as with the Archaeology of the Digital initiative), while in other cases we are interested in the whole archive of an individual or organization (as with Álvaro Siza, and most recently with Bernard Tschumi).

In its first twenty years, the CCA built a collection around postwar modernism, with substantial collections of drawings by Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and others. The archives of Aldo Rossi, John Hejduk, Peter Eisenman, Cedric Price, and James Stirling arrived around 2000, opening another set of reflections on modernism and its aftermath. In more recent years, CCA has expanded this strategy to the archives of historians like Kenneth Frampton, Tony Vidler, and Jean-Louis Cohen. To have both the work of architects and the work of the historians interpreting architecture in the same place creates more opportunities to cut through the topics we’re investigating from multiple directions.

In deciding where to locate archives covering almost forty years of architectural thought and practice, the key factors in the CCA’s favour were the richness of its archival collections, which allow for important ”conversations” among architects including Eisenman, Rossi, Hejduk, Price, and Siza, among others, and the institution’s unparalleled curatorial standards and resources. I am particularly pleased that the most complete repository of archival materials in the world on the Parc de la Villette, from the competition through design, administration, and construction, will now be at the CCA, in a francophone context where scholars can fully access and study these historic documents. – Bernard Tschumi

I am happy that my archives are at the CCA, not only because they will be secure, but above all because they will be searchable online and therefore accessible to researchers, who will be able to dig deeper into some of my research materials and contradict the existing analyses. – Jean-Louis Cohen

The Manifesto exhibition series has been an additional way for us to collect archives of projects that speak to specific, targeted aspects of contemporary debate that interest us: for example, projects by Greg Lynn and Michael Maltzan on how we imagine outer space; projects by Bijoy Jain and Umberto Riva on domestic inhabitation and modes of architectural production; and projects by OFFICE Kersten Geers David van Severen and Go Hasegawa that show their understandings of how the history of architecture influences practice today.

We have also committed ourselves to creating spaces and resources in our collection for the non-white, non-Western voices that have been traditionally underrepresented or cast aside in our field. In ten last years we collected the archives of Aditya Prakash and the practice led by Amancio Williams, along with records of projects by Shoei Yoh. In the coming years we will strengthen this line of acquisition. Much of what we do at the CCA is to try to deconstruct the things that seem obvious or normal in our world, and the nature of our collection itself relies on a set of assumptions that we similarly have to work at breaking apart.

Many international architects have ceded to CCA its own archives. (A.Siza, A.Rossi, C.Price, K.Frampton, J.Hejduk, Ábalos&Herreros, P.Jeanneret, P.Eisenman, …). Why has the CCA become one of the world’s largest institutions in terms of architecture collection?

Martien de Vletter: It has never been the CCA’s mandate or objective to become the institution with the largest architecture collection—instead, we aim to be relevant, or to contribute to a relevant debate. It is not about owning things; it is about what you do with them. This is what guides our thinking about any kind of addition. What we do involves making our collection—archives, but also photography, prints and drawings, and library holdings—available to researchers, but also initiating our own programs.

For example, we recently started a residency program titled Find & Tell, where an invited scholar develops an argument based on an idea coming out of a specific archive, works with our archivists to select material that supports that argument, and writes an article and records a video sharing their findings. We then digitize the selection of material, making it available for additional research. Again, it is not about having the most drawings accessible virtually—instead, we are constantly searching for ways to recontextualize and question, and digitization becomes a tool for doing that, rather than a simple or automatic process. So far the series includes Michael Meredith on the John Hejduk fonds, Peter Testa on the Álvaro Siza fonds, Inderbir Riar on the Van Ginkel Associates fonds, Kim Förster on the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies fonds, Albert Ferré on the Foreign Office Architects fonds, Kurt Forster on the Aldo Rossi fonds, Yu Momoeda on the Shoei Yoh fonds, and Sangeeta Bagga on the Pierre Jeanneret fonds. We will continue the series with Shirley Blumberg on the John C. Parkin fonds, Eva Pratt on the Umberto Riva fonds, and Michelle Provoost on the Aditya Prakash fonds.

We also see all of our output, including our events and publications, as part of our collection. Another recent example relates to the archive of the practice led by the Argentine architect Amancio Williams, which arrived at the CCA earlier this year. In March, we hosted an event in Buenos Aires, “Querido Amancio,” where friends, colleagues, students, and others shared open letters to Williams about his work and significance. These types of conversations and activities around our collection material, which might actually begin with exhibitions and public programs, add to the collection in important ways, and prompt important rethinking of what it contains.

Along those lines, we are interested in exploring issues and demands raised by the architectural community related to new historical perspectives and new readings—for instance, assessing the historical reality to open up the possibility of acknowledging the role of couples, partners, and collaborators. This includes, for example, the question of whether the Amancio Williams archive should include the name of his partner, Delfina. We are eager to pursue these types of reflection, which keep the archives from becoming static.

CCA was born as an archiving centre* and then it was gradually transformed into a museum and research centre for architecture. How and for which reason did this conversion take place?

Rafico Ruiz: The genesis of the CCA is actually not solely its archival mission. From its founding in 1979, it was already conceived as a new form of cultural institution that could be made up of a cluster of elements—research, exhibitions, publications, and the acquisition of relevant archival holdings—that could all reinforce one another. It was, and remains, an exciting, dynamic way of working that makes everything we do into “research” that asks questions and shares them with a broad public.

So from its earliest days, the CCA was precisely conceived of as a “centre”—a gathering location from which to observe and assess architecture as a social practice. Our physical building, designed by Peter Rose in collaboration with Phyllis Lambert, opened in 1989, and gradually provided a setting for this expansive definition of an architectural centre to take shape. Our visiting scholars program began in 1997 and has continued to evolve over the decades. We have actively expanded the scope and formats of these research programs—from enabling deep, traditional historical inquiry into the Baroque early on, for example, to initiating and defining collaborative endeavours that design African-led histories of architecture, in alignment with the CCA’s overall agenda. At the core of the CCA’s identity is a way of approaching research that exceeds a single, narrow definition. It involves scholars, architects, urbanists, artists, policy makers, and others in order to invite in ways of understanding, and questioning, architecture as a public concern.

What is the role or influence of architectural archives in the contemporary architecture culture?

Francesco Garutti: The discussion about the role of archives has been central within institutional debates—and clearly in contemporary art practices, as well—for at least ten years. But the key problem is how to use and activate them: how to transform them into an instrument to read the present, and into a tool for the spatial practitioners today. In 2003, under the direction of Mirko Zardini, the CCA launched a research and exhibition format titled “Out of the Box,” which was reformulated by Giovanna Borasi in 2015. Out of the Box is a format specifically conceived to challenge the very definition of the archive on one hand, and to give form to new dynamic relationships between the archives we house and our varied audiences on the other. Curators in residence explore the collection with us and transform it directly in a show that extends from their points of view. And the curators we work with are not only scholars or academics in a traditional sense; the idea is also to bring in the perspectives of architects and other practitioners, which allows additional readings and resonances to emerge.

This year we investigated the margins of the Gordon Matta-Clark collection at the CCA with Yann Chateigné, Hila Peleg, and Kitty Scott. We invited the three curators to explore and bring forward hidden and less-evident systems of references, to widen our perception of the field of Matta-Clark’s studies and deepen the meaning and legacy of his work today. Somehow this most recent iteration of Out of the Box could be seen as emblematic of the CCA’s approach toward an archive: re-positioning it in a broader context, multiplying its possible interpretations as a way to transform history into active agent in the present.

Beyond Out of the Box, in our exhibition projects we frequently seek out opportunities to commission new work—films, photography, even drawings—that become another way to activate the material already in our collection, by putting it into a dialogue that carries into the present and future.

You are a leading institution within the field of “digital culture” through research programs like “archaeology of the digital”. What are the opportunities and limitations of digitalization in archiving architecture?

Albert Ferré: For an institution that conceives of its collection as a resource for the production of new knowledge, the impact of digital technology and digital culture is multifaceted: it affects the design processes that are being studied and collected, the nature of what constitutes an archive, and the flows of content dissemination and audience engagement. Archaeology of the Digital became an experiment to address these questions. We identified twenty-five projects that incorporated digital tools in innovative and challenging ways around 1990, and we researched, collected, exhibited, and published them. One of the outcomes was a series of small electronic publications that provide an experience of the original digital material while exploring the potential of epub technology.

This experience informed not only our digital publishing program—we are now collaborating with the Harvard GSD on a new series of electronic publications—but also our understanding of how to make the content we produce accessible and operable digitally. Our website, which effectively makes the CCA accessible beyond Montréal, transitioned from a communication tool to an editorial and research platform that foregrounds the presentation of ideas produced at the CCA and treats everything in our collection and every trace of our activity as one body of material available for research. Looking specifically at the collection, and considering that its value relies on the ability to contextualize it and uncover relationships, we constantly generate programs that feed our digitization program with particular readings of a selection of objects—such as Find & Tell, described above—so that both the primary material (the digitized objects) and the readings or ideas they enabled can be shared online.

How is the digital age changing architectural research and its cultural diffusion?

Rafico Ruiz: It may be less a question of change than of what sorts of relationships are being built between these emerging digital technologies and the social role architecture plays. It is precisely the task of unique cultural institutions such as the CCA to mediate those relationships. So our role is to document contemporary architectural digital culture, and to actively participate in it, but also to forecast where it may go and how it can be made accessible to urgent questions about postcolonial urban conditions, social precarity, and other issues that drive our lines of lines of investigation.

There is an inherent physicality to architectural research that the CCA embodies—reams and reams of paper documents that researchers come specifically to Montreal to consult in depth and over time. This is one of the crucial dimensions of our longstanding doctoral research residency program—to give doctoral students from around the world a forum in which to pursue archival research, within a setting that is keenly aware of the absences those archives create. And yet, particularly from the 1980s forwards, the increasing importance of digital technologies in architectural production has also made the very materiality of architectural research more reliant on bits and bytes. Researchers in our collection now can—and must—look over CAD files from, say, 1996, and really experience those digital documents in ways that let them understand what 8-bit colour looked like and lets you see (nor not see). There is a retrospective lens on the digital in architecture that the CCA has helped to craft, notably, as Albert mentioned, with Archaeology of the Digital.

The digital age is indeed an "age,” and one that is open-ended, evolving, and in need of examination and revision. This future-casting is an important part of our research strategy at the CCA: how to ask questions of our shared architectural future? One way we do this is through our Multidisciplinary Research Program, funded by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, that lets us investigate pressing architectural and urban topics at the intersection of a number of disciplines. We recently launched the call for applicants for our fifth Mellon-CCA Multidisciplinary Research Program, The Digital Now: Architecture and Intersectionality. Once this project officially begins, in early 20201, it will convene a group of eight researchers to think collectively on how digital design intersects with the simultaneous relations between race, class, gender, ability, and sexuality. The aim is for the project to bring together a multidisciplinary team of scholars, curators, practitioners, and technologists to question the ways in which digital architectural production and social identity formation are intertwined. This is both the future of the digital age, but also its past. Our understanding of digital change is that of a phenomenon that emanates from the circularity of history, as well as being on a continuum with our shared present.

CCA is more than just an archive. What is/are the mission/s or vision/s of CCA today?

Albert Ferré: We always say that our work is strengthened by our collection, but of course, the question is what the nature of this work is. In that sense, we are not in a different position than any researcher we host, whose objective is to use the collection to support a specific argument. As Giovanna explained in her interview, our mission is to question the world around us—and how we relate to it—from the point of view of architecture, which is not only building but also a way of seeing the world.

With our practice of questioning we aim to challenge the assumptions on which contemporary Western society operates and to consider and foreground other ways of doing, other perspectives. Researching, collecting, exhibiting, and publishing are the means we use to develop and articulate these positions, and to make them public as a way to encourage relevant conversations around topics that we identify as urgent to our present moment. In this sense, researching, collecting, curating, and publishing are interconnected activities that become somehow undistinguishable for us. This blurring of traditional museum practices helps us to mobilize the whole institution around the topics or questions we work on. And we engage key collaborators who share valuable insights and perspectives, not only on the content of our research, but also for reframing our own approaches and pointing out where we should be looking.

When will it be a “CCA c/o” in Switzerland?

Francesco Garutti: The CCA c/o program has been developed to extend our explorations of the global present, investigating key topics in our contemporary society from other perspectives. Incorporating new themes in our agenda is a way of transforming ourselves through work with others. Our c/o program in Tokyo we started in 2018 led to, among many projects, a series of films reflecting on a new approach of architects toward the rural, while in Buenos Aires, the idea of crisis is permeating many of the themes and projects we’re now developing with our c/o curator Martin Huberman. It could be interesting to imagine what are the key topics to explore in Switzerland that make for a kind of manifesto of our present.

The CCA has a close relationship with Switzerland through certain projects, including, for example, the current show The Things Around Us: Rural Urban Framework and 51N4E . To study architectural practice as an expanded ecology, we’re investigating as a key project—among many—the Design in Dialogue Lab at the ETH Zurich, which is directed by Freek Persyn. It is actually an incredibly relevant case study to explore how and why today we are in the need of rethinking the role of the architect in itself, more than just how to make architecture.

And we are happy to have other ties to Switzerland through our researchers and collaborators, and several of the designers we’ve worked with. Two of our most recent publications were nominated in the 2019 Most Beautiful Swiss Books competition: The Museum Is Not Enough, designed by Jonathan Hares, which is a reflection on the role of contemporary cultural institutions today, and Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism, designed by Laurenz Brunner and Geoff Hann, which is a critical analysis on how twelve years of emotional capitalism have been affecting our way of imaging and designing the built environment, from the financial crash of 2008 till today - when a new dramatic crisis is going to probably transform a lot our present.

About :

Martien de Vletter (Associate Director, Collection since 2012) supervises the CCA’s Collection department and is responsible for acquisitions, donations, loans, and collection care and access. Before joining the CCA, she was the chief curator at the Netherlands Architecture Institute (now Het Nieuwe Instituut) and publisher at Sun Architecture. She has recently published several articles on the preservation of born-digital collections.

Albert Ferré (Associate Director, Publications since 2012) oversees the CCA’s print and electronic publishing program, along with its online editorial platform. Trained as an architect, he was previously editorial director of Actar (Barcelona / New York) and managing editor of the Prince Claus Fund Library (Amsterdam).

Francesco Garutti (Curator, Contemporary Architecture since 2017) supervises the Exhibitions and Public Programs department at the CCA. Using art and architecture to activate cross-disciplinary research, for the CCA he has recently curated the projects The Things Around Us: 51N4E and Rural Urban Framework (2020) and Our Happy Life: Architecture and Well-Being in the Age of Emotional Capitalism (2019), and directed the “Out of the Box” program on the Gordon Matta-Clark collection (2019–2020).

Rafico Ruiz (Associate Director, Research since 2019) oversees the Research division of the CCA, including the Mellon-CCA Multidisciplinary Research Program, the Research Fellowships, and the doctoral student and masters student programs. He holds an interdisciplinary PhD in the history and theory of architecture and communication studies from McGill University, and has published widely on settler colonialism, infrastructure, and architecture in the circumpolar world.

Dossier: «Archives of architecture»

On the role of archives and their absence - Editorial by Yony Santos & Cedric van der Poel, November 2020

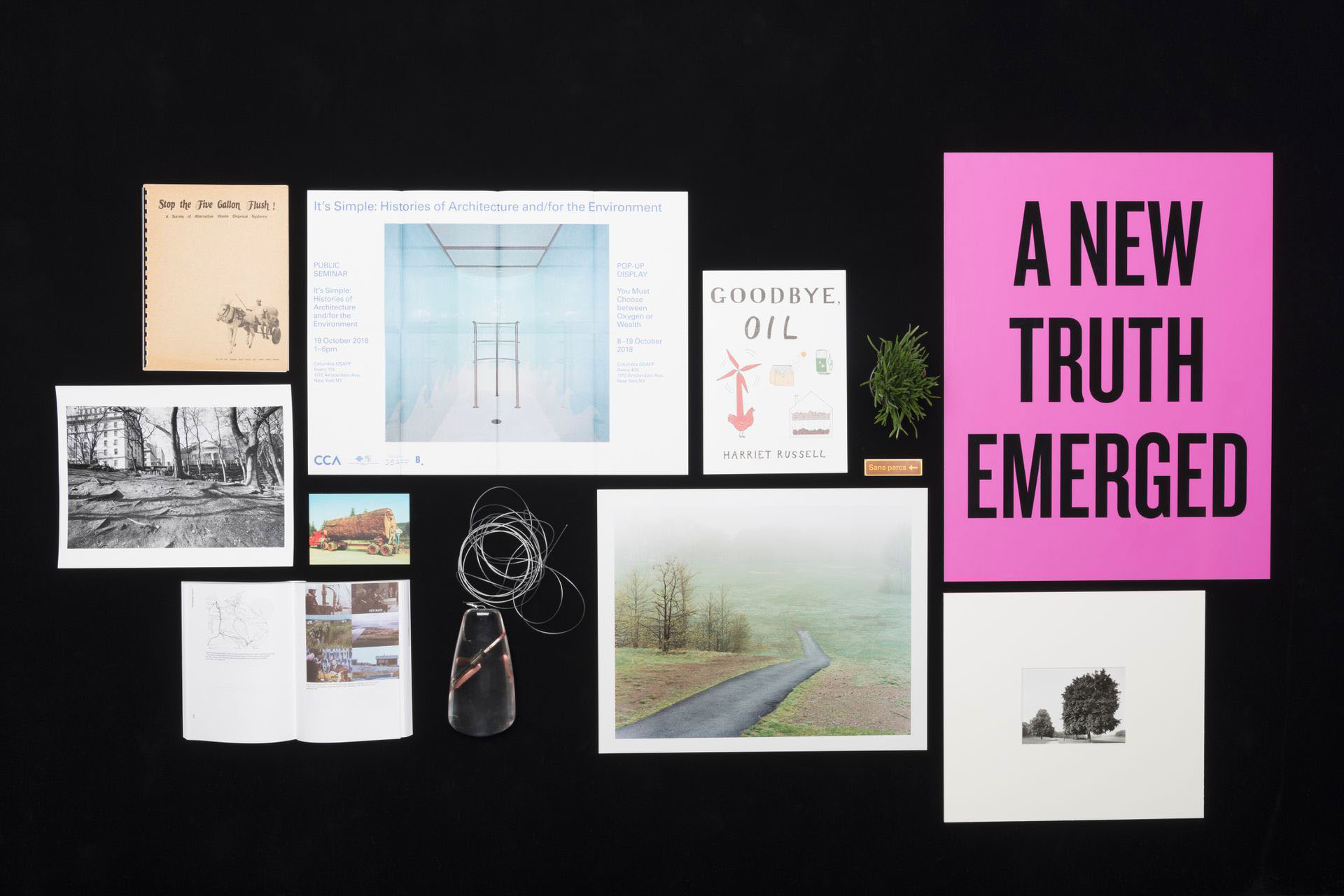

![Alcune mie architetture (v.12-pp.[46]-[47] of Il libro azzurro, 1972. Fonds Aldo Rossi, 1943-1999. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California (880319)](https://espazium.s3.eu-central-1.amazonaws.com/files/2020-11/P25186%20880319%20%20notebook%2012_3000x3000.jpg)