Architecture’s Afterlife: Breaking the Profession that is Breaking the Planet

With 40% of graduates in Europe not choosing to work as architects and less than 1% of buildings in the world being zero-carbon, architecture is betraying its promises. The cry raised by Dr Harriet Harriss and Roberta Marcaccio calls for an urgent overhaul of education and practice.

➔ In italiano : L'aldilà dell'architettura: Rompere la professione che sta distruggendo il pianeta

➔ En français : Au-delà de l'architecture : déconstruire la profession qui détruit la planète

➔ Auf Deutsch : Jenseits der Architektur: Den Beruf aufbrechen, der den Planeten zerstört

For most of the twentieth century and at least a good fifth of the twenty-first, architecture schools around the world have promoted a dangerously dishonest ideology—that architecture degrees should be taught as if they were entirely vocational—focused exclusively on the production of buildings, and not a powerful pathway towards a plethora of other professional possibilities.

What makes this old ideology dangerous is that this protectionist, self-serving, and self-aggrandizing perspective poisons our pedagogies and our planet, its peoples, places, and all other forms of life upon which our collective existence depends. This is evidenced by the fact that the world's estimated three million architects[1] have so far succeeded in creating less than 2500 zero-carbon buildings[2] – well under 1% of the built environment worldwide. Prescribing a building in response to every ailment is propaganda, not pedagogy, because buildings account for 35% of total resources, about 40% of energy usage, 12% of the world’s drinkable water, and produce 40% of total carbon dioxide gas emissions – and that’s just for starters. We seem to forget that without a planet, there can be no profession.[3]

« The idea that architectural education should focus on the production of buildings is a protectionist, self-serving and self-indulgent perspective that is poisoning the planet, its people and its places. »

If schools continue to ignore or deliberately underplay the multi-sectoral transposability of an architecture degree, students will continue to graduate without fully realising their true potential – whether they choose to practice as architects or not. Indeed, as we argue within this article, it is a professional, personal, and economic injustice that students are largely unaware of how their architectural education predisposes them to have successful careers beyond architecture – as planet-saving protagonists or otherwise. We must begin to hospice architecture's delusions and redirect our attention towards rebuilding architectural education as a planet-prioritising profession, one whose output « might be a building » – (as well as many other things, depending on what is needed or possible) rather than « must be a building ».

Ending a toxic relationship

An architecture degree demands a five- to nine-year commitment – twice as long as most other degree disciplines. The fact that students are willing to make this kind of commitment is a testimony to architecture's enduring appeal and students' passion and dedication. The widely held assumption is that, once this training has ended, graduates are expected to find work in private practice, typically in an urban center, working on buildings commissioned by those who can afford it. In reality, architecture has one of the highest dropout rates – well over half of those who enroll will leave before graduating and without any exit qualification – with women and minority students disproportionately represented among these departures. Even among those who choose to qualify and pursue a career in architecture, these gender and minority inequalities persist and even get worse over time, indicative of the inherent structural and systemic discrimination in the education system and the sector.

« Presenting architects as ‘designers of form’ is an unsustainable proposition in the face of the climate emergency that is leading us to question the old paradigm of linear progress and, with it, the continuous production of buildings. »

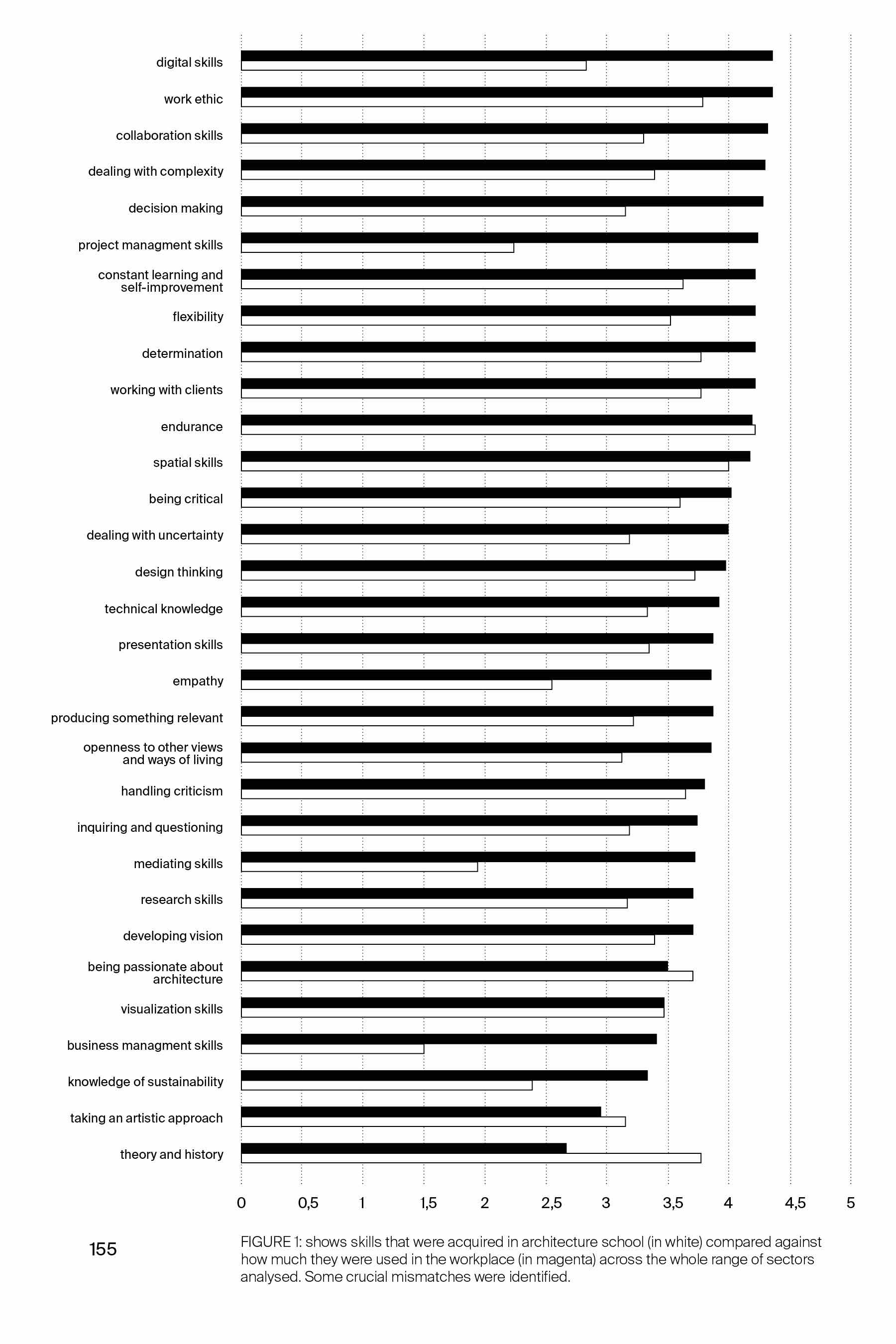

If a toxic relationship is defined as one that ‘causes distress or harm’, involves ‘emotional, psychological, or physical abuse and can make you feel unsupported, misunderstood, or demeaned,’ then the ongoing student mental health crises, the culture of all-nighters, the (courtroom evoking) design ‘juries’, the financial disincentives such as the below-median graduate salaries (Related article: Geneva's architects are angry) -and in some countries, the crippling debt- seem justification enough for student ‘veterans’ of architectural education to want to to put an end to a toxic relationship. (Fig. 1).

Old guard versus avant-garde

To date, a wealth of scholarly and journalistic analysis (including our own) has played a critical and, at times, proto-therapeutic role in diagnosing how it came to this.[4] More recently, however – and thanks to a €331.887 Erasmus+ research grant[5] which recognised and supported the seriousness of our concerns – our research has focussed on the opportunities that exist beyond the narrow view of architecture commonly taught and practiced. Consequently, this article is directly informed by findings from the Erasmus Plus study (2019-2023) and from two recent books that the authors co-edited: Architects After Architecture: Alternative Pathways for Practice (Routledge, 2020) and Architecture's Afterlife: The Multi-Sectoral Impact of an Architecture Degree (Routledge, 2024), the latter of which offers a synthesis of the Erasmus Plus study’s findings. Both the books and the research underscore the need and desire for architects to adopt new ways of working, looking beyond the arbitrary limits of our profession to address the world's challenges and opportunities. Moreover, both books provide a testimony-based road map as to how to achieve this.

Neither the study nor the books petition to break architecture as a means to destroy it. Instead, they argue – as does this article – that it has become an unequivocal necessity to break apart architecture and reconfigure its priorities, processes, and end products within education and practice rather than let it continue to break the planet.

Front runners, not failures

Datasets drawn from different countries and from a diverse array of timeframes and sources showed that almost 40% of architecture graduates across Europe and the USA choose not to practice as architects.[6] By ‘breaking up’ with the profession – or at least rejecting its self-limiting propaganda – this surprisingly large but vastly overlooked cohort is making significant contributions to various sectors, such as activism, humanitarian aid, video games, politics, and technology. While it is not uncommon for graduates of any discipline to work in a sector unrelated to their degree subject, this is not what is expected of graduates of so-called 'vocational' degrees such as medicine, law, and architecture.

« It is a professional, personal and economic injustice that students are not aware of the potential of their architectural training, predisposing them to successful careers beyond architecture, whether they save the planet or not. »

The talent hemorrhaging in architecture schools is seen as a personal rather than a pedagogical failure and a clear mandate for the latter's reform. Schools' unending refrain, ‘What is the point of studying architecture if you are not going to become an architect?’ is grafted onto the profession – whose networks, memberships, media, medals, and awards systems form a Mobius strip of stifling exclusivity and autoregression. This also accounts for why architecture schools and professional accreditation bodies have shown no interest in recording or mapping the career destinations of those who have 'left' the profession. However, by perpetuating this propagandistic narrative, schools fail to recognise the impact that architecture graduates have on other sectors, unwittingly undermining the 'value' of an architecture degree and, in the face of declining student numbers, the survival of their programs and institutions, too.

« Young architects are prioritising public needs, moving towards more socially and ethically responsible practices and describing their desire to have a (real) impact on a planetary scale and at a much more effective rate than a building. »

As both the aforementioned books and the Erasmus+ study contend, the remedy is simple: create assessment and alumni tracking systems that recognise these graduates as front runners that should be celebrated rather than failures who deserve nothing for ‘abandoning the profession’. This means finding ways to diverse pathways as a sign of cross-sectoral success and championing the ways in which these graduates re-purpose their architectural knowledge, skills, and behaviours to address shortages across all sectors in employment conditions that are transient, unstable, and vulnerable to political, social, economic and environmental upheaval. What follows is a synthesis of the key findings of both the books and the study.

« Starchitects » After Architecture?

If big data was consistently effective in the rarefied art of persuasion, we wouldn’t be facing an existential crisis – professional or planetary – at this point in our history. This accounts for why we focussed on ‘qualitative’ data such as interviews or ‘testimonies’ within the first book, Architects After Architecture, which we co-wrote and edited in collaboration with Rory Hyde. By profiling 40 practitioners who have used their architectural training in new and resourceful ways, we wanted to provide graduates with evidence-based exit strategies and effective efforts at reimagining architecture from the margins of mainstream practice. Two individuals who took the exit ramp include Matt Jones, who describes how his architecture degree helped him assume the role of principal designer at Google AI, and Miriam Bellard, who, after studying architecture in New Zealand, went on to become the Art Director for Visual Development at Rockstar Games, designing virtual architectures for blockbuster video games such as Grand Theft Auto and Red Dead Redemption.

« The teaching of architecture needs to be deconstructed so that a building is just one professional response among many... »

Both Matt and Miriam described their desire to effect change at a planetary scale and a far more efficient rate than one building at a time as the reason they chose to transpose their skills into the technology sector and become true front runners within their adopted specialisms. As of November 2024, Grand Theft Auto V has sold over 205 million units worldwide since its release in 2013 and is considered one of the best-selling video games of all time.[7] This level of ‘global impact’ goes far beyond what any ‘starchitect’ portfolio packed with significant commissions, monographs, media coverage, and industry awards could ever claim to have achieved.

Architectures that Prioritise Public Need

A consistent theme among the architects who chose not to take the exit ramp but instead remain on the margins of architecture and work to radically reimagine it was their shared commitment to proving that more socially and ethically responsible and responsive ways of practicing architecture are possible.

One such example is Rotor, a cooperative based in Brussels, who realised that to address climate collapse, they needed to confront architecture’s troubling relationship with waste. To do so, they focused on deconstructing rather than constructing buildings and then repurposing the materials and components elsewhere, with outputs ranging from design, research, exhibitions, books, and economic models to policy proposals.

« The very large and largely marginalised group of architecture graduates who do not choose to practice as architect contribute significantly to various sectors such as activism, humanitarian aid, video games, politics and technology. »

Working beyond the materiality of buildings, Chris Hildrey applied his urban and civic thinking to the question of homelessness, developing a digital tool, Proxy Address, to offer a virtual address to the unhoused as a means to secure their access benefits, bank accounts, identification, a job, a doctor and receive ‘real’ mail – all key services otherwise removed at the time of most need. Additionally, Malkit Shoshan, whose agency FAST – the Foundation for Achieving Seamless Territory – investigates the impact of UN peace missions on local communities and the environment, has developed a model for transforming UN bases into catalysts for local development.

Learning what isn’t taught

The second book, entitled Architecture's Afterlife, is based on the findings of an Erasmus+ strategic partnership of the Royal College of Art, KU Leuven, Politecnico di Torino, University of Antwerp, University of Zagreb, Polytechnic University of Valencia, with the European Association for Architectural Education (EAAE) as associate partner. It examines why almost 40% of European architecture graduates don’t choose to work as architects, maps the sectors to which they migrate, and identifies the transferable skills acquired during their degree programs that prove most helpful in their new careers. The research highlighted ‘transversal skills’ – such as communication, team-working, client interactions, problem-solving, learning, planning, and organisation – as relevant across most sectors. It also highlighted that graduates with an architecture degree possess the ability to meet skills shortages in other sectors (Fig.3).

Related article : The challenges of architectural education in Europe according to the EAAE

One of the key insights, however, is that the transversal skills that graduates found most helpful in other sectors were not those that they had been explicitly taught but those that they had developed in response to and in support of their educational experience - from learning to have a ‘thick skin’ or to ‘be relentless’[8] - for better or for worse. The study’s quantitative and qualitative data also pointed to how architecture's inherently multidisciplinary and ambiguous nature – apparent even in the language used to describe it in the guidelines that regulate it – seemed to give students the ability to manage complexity and deal with ambiguity. The problem, however, is that while architecture students acquire these skills, they are not explicitly taught in the curriculum, nor are they recognised as important by the institutions that assess them

Changing professional accreditation, changing Higher Education Policy

The study’s findings call for a radical reappraisal of graduate qualifications – one that, through a better understanding and emphasis on transversal skills, can increase graduate employability and sectoral mobility, both to address current skills shortages and to equip the future workforce better to meet the challenges ahead. To achieve this, the study makes several proposals, including developing an EU-wide, cross-sectoral rubric to define skill typologies and behavioural attributes, including emotional, social, soft, and technical competencies. It also suggests that educational institutions should make the teaching of transversal skills explicit in their disciplinary assessments and degree transcripts, if not also recognizable as stand-alone micro-credentials. Employers - independent of their sector - should take a more active role in maintaining and developing the skills of their employees, using the workplace as a classroom and partnering with educational institutions.

« Academic protectionism explains why architecture schools and professional accreditation bodies show no interest in mapping the career trajectories of those who have ‘left’ the profession, ignoring the ‘value’ of a degree in architecture and the impact of that career in other sectors. »

Companies with established R&D units could even be allowed to obtain education licenses to offer research degrees, for example, by expanding the European Professional Doctorate (EPD-EU),[9] or the RMIT Practice Research Programme.[10] In this way, education and research in practice could become more immersive, relevant, and affordable for researchers and employees willing to engage in lifelong learning, unlearning, and relearning.

The real ‘value’ of an architecture degree

The combined insights from both the books and the study suggest that contrary to conventional thinking, the most unique, most transposable, and most universally sought-after qualities of the discipline are those that students acquire in order to design a building and not necessarily in the realisation of a building itself. This is crucial because by overemphasising the production of buildings as the primary if not sole endeavor, architects retreat from recognising where their true value is situated and misapprehend that their increasingly poor pay, precarious position, and planetary poisonings can only be remedied by designing ‘better’ buildings and not by re-designing a ‘better’ pedagogy and profession. Perhaps the “elephant in the room” is that architects play a very small role in architecture in the first place – outnumbered by the builders, engineers, contractors, developers, and other design consultants that are also involved – and, more often, better paid. Secondly, billing ourselves as form-mongers is an unsustainable proposition in the face of the climate emergency that is causing us to question the old paradigm of linear progress and, with it, the continuous production of buildings that, once halted as it has to be, will surely put us out of work.[11]

If we are brave enough to look “beyond the building”, we see that architecture is a discipline that combines synthesis (the ability to bridge different forms of knowledge, communities, and viewpoints), vision (bringing these viewpoints together into a coherent narrative) and pragmatism (making things happen by navigating existing technical, political and legal frameworks). These qualities point towards a certain flexibility of mind which is what is most unique about what we do, and it is also an urgent skill for the century ahead because the great challenges we face do not fit into neat disciplinary silos but straddle the messy space between politics, economics, ecology, culture, and spatial thinking, calling for the ability to adapt, navigate uncertainty and engage with different forms of knowledge.

« The most useful skills acquired during their training are communication, teamwork, interaction with clients, problem-solving, continuous learning, planning, and the ability to manage complexity and deal with ambiguity. »

In a subsequent article, the authors will draw on their current research to further explore how architects can best use these skills to facilitate transition within the post-anthropocene.

Dr. Harriet Harriss (ARB, RIBA, (Assoc.) AIA, PFHEA, Ph.D) is a tenured professor at Pratt School of Architecture, where she served as the Dean from 2019-2022. An award-winning educator, writer, and UK-qualified architect, Dr. Harriss has established a global reputation for her books and publications that position social justice and ecological justice as pedagogic and professional imperatives. A Clore Fellow and British School in Rome Academician, Dr. Harriss’ most recent awards include an IPA (Institute of Public Architecture) Writer in Residence (Summer 2024) and an Arctic Circle Residency (Spring 2024). harriet-harriss.com

Roberta Marcaccio is a research and communication consultant, an editor, and an educator whose work focuses on alternative forms of design practice and pedagogy. Her publications include the forthcoming ‘The Hero of Doubt’ (MIT Press, January 2025) and ‘The Business of Research’ (AD, Wiley, 2019). Roberta is a Graham Foundation grantee and has been awarded a Built Environment Research Fellowship by the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 and a Research Publication Fellowship by the AA. www.marcaccio.info

Notes

[1] The Union internationale des Architectes; (UIA) - the only international non-governmental organisation that represents the world's architects estimates there are approximately 3.2 million architects in the world today.

[2] According to the World Green Building Council (WorldGBC), there are currently 500 net zero commercial buildings and 2,000 net zero homes around the globe. Source: https://worldgbc.org/reports/

[3] See: ‘The Future of Architecture is for other Species.’ [Chapter in] Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change, 2023

[4] Alice Moncaster, Horizons 2034: The Environmental Challenge, RIBA, 2023.

[5] Source: https://erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu/projects/search/details/2019-1-UK01-KA203-062062

[6] The Erasmus+ study indicated that while 62% of European architecture graduates practise as architects, of the 38% who choose to leave, 21% combine design and construction of buildings with other architecture-related work; 10% choose to work in sectors related to architecture such as the creative industries (e.g journalism), and 7% moved into non-related sectors, such as politics. The study surveyed 2637 respondents living in 65 countries (with 95,3% of the respondents coming from 32 European countries). It also conducted 48 in-depth interviews with architecture graduates practising as architects, working in related sectors, the creative industries sector, and other sectors. See also Bob Sheil, ‘Afterlife’ in, Radical Pedagogies: Architectural Education & the British Tradition. Harriet Harriss, Daisy Froud (eds.). RIBA Publications, 2015.

[7] Source: GTA 5 cumulative unit sales worldwide 2015-2024

[8] Source: How to Survive (and Thrive!) in Architecture School

[9] The EPD-EU is a uniquely tailored, practice-based programme for owners, entrepreneurs and senior managers at CEO and Director level working in a global business environment. This qualification is academically equivalent to a traditional PhD in business. Reflecting on their own practice, nominated EPD-EU candidates typically take an existing concept or problem in their industry, conduct the research and recommend proposals or solutions. See: https://mbalondon.org.uk/courses/european-professional-doctorate-eu/

[10] With programmes across North America, Australia and Europe, the Practice Research PhD at RMIT invites architectural practitioners to reflect on their creative practice and articulate the contribution it makes to the discipline as a whole as well articulating insights into emerging issues and proposing agendas for future practice and research. See: https://practice-research.com/about

[11] See: Jeremy Till, ‘Architecture After Architecture’, [in] Harriet Harriss, Rory Hyde, Roberta Marcaccio (Eds), Architects After Architecture: Alternative Pathways for Practice, Routledge, 2020, 29-37.

Relevant publications by the authors

- Barosio, Michela, Dag Boutsen, Andrea Čeko, Haydée De Loof, Johan De Walsche, Santiago Gomes, Harriet Harriss, Roberta Marcaccio et al. « Architecture's Afterlife: The Multi Sector Impact of an Architecture Degree. » Routledge, 2024.

- Harriet, Harriet. « The Future of Architecture is for other Species. » [Chapitre dans] Designing in Coexistence – Reflections on Systemic Change, 2023.

- Harriss, Harriet, Ashraf M. Salama, et Ane Gonzalez Lara, éd. « The Routledge Companion to Architectural Pedagogies of the Global South. » Taylor & Francis, 2022.

- Harriss, Harriet, et Naomi House, éd. Design Studio Vol. 4: « Working at the Intersection: Architecture After the Anthropocene. » Routledge, 2022.

- Harriss, Harriet, Rory Hyde, et Roberta Marcaccio, éd. « Architects After Architecture: Alternative Pathways for Practice. » Routledge, 2020.