Notes on the culture of models in Switzerland in the 20th and 21st centuries

What is the role played by the architectural model in Swiss design culture of the 20th and 21st centuries? Is it possible to assert the existence of a specificity – or even an exceptional character – in the practice of the model in Switzerland? These questions are prompted by the observation of a significant presence of the architectural model in the practice and teaching of architecture in Switzerland.

What is the role played by the architectural model – meaning in its physical, tangible, three-dimensional form – in Swiss design culture of the 20th and 21st centuries? How has this extraordinary and polysemic device been utilized – and with what objectives – in the different disciplines and by the various agents that take part in the theory and practice of construction? Is it possible to assert the existence of a specificity – or even an exceptional character – in the practice of the model in Switzerland?

These questions, to which we will attempt to offer a partial answer – or rather a trail for their critical analysis – on the pages that follow, are prompted above all by the observation of a significant presence of the architectural model on a small scale in the practice and teaching of architecture in Switzerland over recent decades. In fact, as is well known, for many Swiss architects it is an indispensable practical and/or critical tool in one or more of the moments that constitute the design process, from the idea to the gestation, testing and visual formulation of the results achieved. Along parallel lines, it has an important place in architectural teaching at many Swiss schools, increasingly in relation today – of antagonism or cooperation – with the progress of computer-based tools.

Thus far, the scenario might seem quite comparable to that of other European countries. And, after all, at first glance it seems hard to surgically separate the specificities of Swiss use of the model from its international deployment, also due to the fertile exchanges that have always nurtured Swiss culture. Instead of trying to define a closed, exclusive system, however, we can attempt to identify certain themes and case studies, from small to large scale, that are clearly not exhaustive but can offer an outline for research. All this, in perspective, with the goal of fostering knowledge and above all a conscious valorization of the culture of the model in Switzerland, which could lead to interesting results.

Reliefs and Stadtmodelle. The model as a tool of knowledge and identity

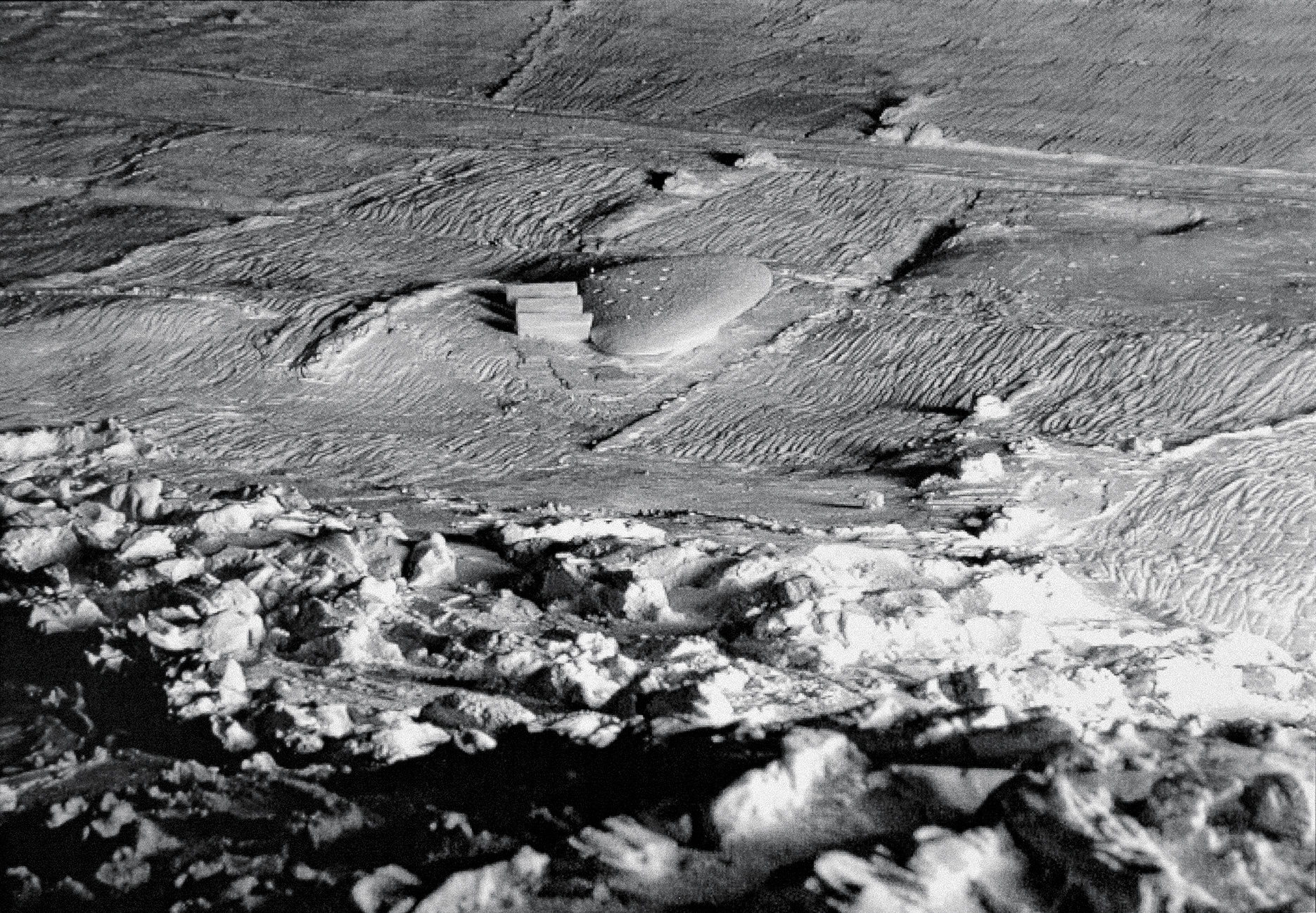

To theorize a culture of the Swiss architectural model, we cannot overlook other types of scale models. They include, first of all, topographic models, three-dimensional devices of representation of the world which the geometric and territorial complexity of the Swiss landscape has required, stimulated, rendered indispensable and particularly ambitious.

The construction of reliefs of the Swiss mountains made particular advances in the 1700s, leading to remarkable specialization towards the end of the century to follow, when progress in systems of measurement and representation – combined with the growth of mountaineering, geology, photography and other disciplines – boosted expertise in this sector, transcending the forced and scarcely intuitive representations of traditional maps.1 Like the latter, besides its practical functions the topographic model had other objectives or consequences, including the construction of a sense of national identity in a country composed of different ethnic groups, languages and cultures.2

One of the oldest conserved reliefs is the one made across over 20 years of labor by Franz Ludwig Pfyffer von Wyher (1716-1802),3 lieutenant general of the French army, who in Paris came into contact with the prestigious school of model makers dating back to the days of the Sun King.4 His work, also admired by Napoleon,5 was followed and surpassed by that of figures like Joachim Eugen Müller (1752-1833), Albert Heim (1849-1937), Xaver Imfeld (1853-1909), Carl Meili (1871-1919) and Eduard Imhof (1895-1986), among others.6

In spite of the historical decline after the Napoleonic era of this type of model as a tool of knowledge of the territory,7 its role still seems to be precious today. For example, for students of architecture the construction of reproductions (though simplified) of parts of the territory represents an exercise that leads to comprehension of the Swiss context, which is also an initial “physical” approach to the concrete reality of architecture and territorial planning. In other areas, such as those of exhibitions or tourism, the communicative power of the topographic model is confirmed and even increased today thanks to interaction with multimedia content.8

Models that represent urban centers are also very widespread in Switzerland, with a centuries-old tradition that was originally linked to the “physical” representation of power9 and then spread in various directions.10 One of the most important is the Stadtmodell of Zurich, made towards the end of the 1960s, which reproduces the city’s (approximately) 55,000 buildings on a scale of 1:1000. Not only due to its size (over 100 sqm), it stands out as a symbol of collective heritage and a tool of concrete operative utility. Open to the public free of charge, the Stadtmodell is a tourist attraction but also a civic one, capable of making the forma urbis perceptible (and therefore more vividly shared), demonstrating the value of the urban model as a device of knowledge and construction of identity. This civic character then meets specialization in a technical function, since the model – now supplemented by a digital version – is utilized by the municipal administration to test the insertion of new buildings in the urban context.11

The architectural model in Switzerland: a story yet to be written

While it seems possible to assign topographic and urban models a role in the process of awareness of Swiss identity and territory, it is on the scale of architectural design that the practice of the model takes on a wider range of meanings and purposes in Switzerland. For the architect, in fact, this “object” plays multiple roles: traditionally, it constitutes a tool of representation used to display, in three dimensions, a version of a project on a smaller scale (for a client, the jury of a competition, an exhibition, etc.); or it can be a tool of testing in the various design phases, from the outset of an idea to the final evaluation of construction techniques. It can also become a device with great autonomy with respect to the worksite, an artifact that responds to its own logic, touching on the disciplinary statute of architecture or on artistic reflections, to a greater or lesser extent. These nuances are also recorded in the different terms used to define the “model”: maquette, plastico, relief, mock-up, and so on.

As we have already seen in the reliefs of the Alps, for the architectural model too various endogenous aspects and impulses from abroad can come into play, still leading today to hybrid and diversified forms in Switzerland. The question arises: do specific factors exist, nonetheless, that may have nurtured the practice of model making in Switzerland?

Certain parallels are perilous and hence to be suggested only timidly, though they should not be ruled out. The theme of miniaturization, for example, is widespread in various forms of Swiss culture: just consider watchmaking, precision mechanisms, model railroads; of the miniature theme parks (see Swissminiatur, which though based on the Dutch Madurodam park has become a typically Swiss institution); the tradition of carved wooden Chaletmodelle (the so-called Hüselischnitzerei);12 and, more generally, the echoes of a widespread culture of crafts, which people already encounter during their school days. Is there a connection between this type of artisanal/industrial/material/popular/tourism culture and the practice of architectural model making?

Shifting towards professional practice, we instead have to consider certain more concrete factors, such as the level of fees and the organization of work, which with respect to other countries set higher standards and thus permit the “official” and programmed introduction of the model in the working process. This “privileged” condition is also behind the spread of model-making workshops inside large architecture firms, in parallel with the presence of specialists in this area – such as the one founded in 1948 in Zurich by Will Zaborowsky13 – where traditional crafts are combined with data processing tools.

But a history of the architectural model in Switzerland has yet to be written, and in the most recent monographic research the examples mentioned are few, and necessarily limited to certain outstanding cases. Nevertheless, it would be worthwhile to make a wider study, to monitor this type of material, conceptual, technical, scientific and artistic expression across the centuries, and from the start of the 20th century in particular, when the practice of the model too was impacted by the immense epistemological breakthrough produced by the advent of the avant-gardes. For example, thanks to the absorption of practices such as Dada’s use of collage/assemblage, or the use (in the wake of Schwitters) of objets trouvés to expand the imagination of architects with new impulses arriving from the everyday sphere,14 the maquette was “downgraded” – with the aim of “breaking away from linguistic habits, to reject any conventions, any academicism”15 – while at the same time it took on an autonomous, poetic and artistic value, leading to a reversal of the very concept of architectural modeling. Hence, from the reproduction of an existing or envisioned building, architects began to conceive of their works based on the impressions conveyed by the model itself.

These reflections bring to mind many possible paths of research. For example: how did such a conception of the act of making models penetrate Switzerland from the 1920s onward? What type of methodological and cultural hybridization took place between the tradition of the Écoles d’Art and the Kunstgewerbeschulen, and the pedagogical methods that appeared in Europe? We can consider the influence of the Bauhaus in Switzerland, but also the penetration in the same era of the Russian avant-gardes through the magazine ABC, which published the models produced at the Vkhutemas in Moscow,16 as well as the works of Vantongerloo, Naum Gabo, the Proun series by El Lissitzky (“illusions of tensions between bodies plastically interpreted in infinite space”)17 and Moholy-Nagy.18

These and many other trails would lead to exploration of the use of the model by Swiss designers, obviously also including Le Corbusier, the maker and “instigator” of hundreds of models in which we see a mixture of his artisan background at La-Chaux-de-Fonds with the stimuli of cinema, photography and the avant-garde plastic arts.19 Or Max Bill, a reference of great interest not only, and perhaps not primarily, for his effective use of the model in architectural design (which was far from excessive), but also and instead for his multidisciplinary and all-around approach to the project, on various scales and of various types. Bill, in fact, conducted artistic research at 360 degrees, from graphic design to architecture, sculpture to urban furnishings, painting to the design of objects, demonstrating the potential of the leap of scale in a coherent way with respect to the principles of the Gestalt and gute Form.20

In the decades to follow, the meanings of the maquette increased in relation to contemporary art, reaching a (provisional) apex in the 1970s, when the theorized independence from the worksite – in its versions as drawn architecture, cardboard architecture, etc. – led to the heightened impact of the conceptual model in parallel with the power of drawing, also with clear consequences on the art market. Not by chance, in 1982 the Centre d’art contemporain in Geneva hosted the exhibition Maquettes d'architectes,21 effectively following the show organized six years earlier at the IAUS in New York, titled Idea as Model.22 The model thus became a “fetish for collectors,”23 but also (and more profoundly) confirmed its role as a device through which to investigate architecture, above and beyond its construction.

The bond between contemporary art and the model would lead us much further, not only for the “trespasses” of many artists (see the German Thomas Demand) into the world of the architectural model, but also due to the multiple influences of contemporary art – in its aesthetic, cultural and (not lastly) commercial aspects – on the world of architecture, especially in German Switzerland. One very particular case, for example, is that of Peter Märkli, whose maquettes – study models in small format, assembled with humble materials and in an apparently rough way – are the result of research that blends a marked tendency towards geometric abstraction with reflections on the expressive potential of material. In certain ways, these minute three-dimensional “sketches” can be seen in relation to the plaster of Paris reliefs by the sculptor Hans Josephsohn, with whom Märkli worked at length, and from whom he absorbed – starting in his days as a student at ETH – the idea of coming to terms with architecture also through the approach of the sculptor, enriching his works with material, conceptual and procedural debts from outside the discipline.24

From directors to collectors. The model in the work of Herzog & de Meuron

Among Swiss contemporary architects, Herzog & de Meuron are certainly the most famous for their almost obsessive use of models as a design tool. Nevertheless, for the architectural duo the use of the model developed in a much more original way.

Towards the end of the 1970s, Herzog & de Meuron used models as devices for the control of form, but in a context of video and photography,25 as sets in which to film in order to product “images of things that could become architecture.”26 Besides experimentation driven by the video art of the time, these scenes in which real people acted, with the aim of “drawing attention to our work, to its potential,”27 contained a rejection of the most widespread experiential and functional modalities of the maquette,28 and above all embodied a programmatic reversal of perspective. The observer in this case was forcefully deprived of visual and physical dominion over the model (the giant looking at a miniature building), and stimulated to come to terms with scenes of possible reality, which are part of the reflections on the image made by the two architects, but also of the conviction that the reality of architecture exists whether or not it is constructed, relying on an autonomy comparable to that of a work of art.29

Later, however, the models of Herzog & de Meuron have taken on an increasingly important design role through a leap of reproduction. Rather than a single miniature copy, the models (often based on a sketch by Herzog)30 have become multiple, organized in series, so as to have infinite alternative realities from which to draw in a process of selection. This is not without precedent, but besides being decisive in the development of certain buildings,31 this use of the maquette and become a central part of the firm’s display narrative – another area of its research, at least since the well-known exhibition at Centre Pompidou curated by Rémy Zaugg32 – reflecting the growing international interest in the exhibiting of architectural models, which after all belongs to a long tradition.33 In 2002 a selection of “little models” was thus at the center of the exhibition curated by Philip Ursprung at CCA in Montreal,34 which actually decreed a decisive change of status for objects previously considered Abfall, rubbish.35 Along this pathway, we can also come across the creation, in 2015 in Basel, of the The Jacques Herzog und Pierre de Meuron Kabinett, an institution balanced between an in-house archive, a private collection and an exhibition space.36

Peter Zumthor: the model as an independent dimension

Others have already written about the exceptional character of the models of Peter Zumthor,37 and various exhibitions have featured them.38 Within the limits of this essay, we are interested in underlining the fact that they are emblematic, in an almost extreme way, of one of the most original values of the model for contemporary architecture, which consists in become a device of project development (especially in the early phases) that is autonomous with respect both to drawing and to a prevalently theoretical approach. The implicit freedom of the act of modeling, i.e. of shaping a subject still partially indefinite in three dimensions through a composite range of materials, leads in fact to a cathartic liberation both from the “structures” of technical drafting and from the original theoretical preconceptions. This emancipation therefore fosters a phenomenological approach that can suggest sudden changes of direction to the designer, caused precisely by the introduction into reality of an object that in spite of its approximate character (or perhaps thanks to it) constitutes an indispensable counterpart, since it is already immersed in the world of things.

This dialogue is stimulated in a variety of ways. A recurring factor, for example, is the attempt to employ techniques and materials similar to those of true construction in the model, experimenting with miniature worksites in which the degree of consistency with the laws of reality is nevertheless variable. One emblematic case is that of the Bruder Klaus Field Chapel in Wachendorf, whose internal space is the result of artisanal research on the relationship between form and counter-form, positive and negative, conducted by using models on different scales. Precisely the gap between the dimension of reality and that of the “fetish” introduces unpredictable technical, semantic and sensorial shifts that act as stimuli. In this beneficial effect, we can perceive a decisive conceptual reversal with respect to the warnings on the discrepancy between actual scale and the scale of the model traditionally expressed by Vitruvius, Leon Battista Alberti and Scamozzi.39

Besides pointing to the influence of artists like Joseph Beuys, Richard Serra, Walter De Maria and Michael Heizer, among others, the accent on materiality possessed by these “atmospheric” models thus sets them profoundly apart from those of many other colleagues, in whose work the essential character implicit to a certain type of maquette instead becomes a preset goal, rather than a starting point or a proving ground.

Structural research

Christian Kerez acts on a different level of interpretation. As in a sort of X-ray, in his models the entirety of the architectural body can only be glimpsed, because the representation concentrates on certain specific generating elements, often coinciding with the structural members or circulation routes. According to Kerez, thanks to the model it becomes possible to “understand complex phenomena by simplifying them,”40 in keeping with an indirect reproduction of reality that has its own reality and helps us to see the idea behind a building.

In the project for the Salzmagazin school building in Zurich (1997), for example, the accent on circulation produces a model composed of the overlapping of box-like parts, achieving a result similar to the Catasta of Alighiero Boetti (1966), but in this case solidly linked to the functional dictates of the program.41 Often, what come to the fore are the acrobatic structural relationships, reproduced with different materials that pierce the invisible space and seem to combine the Swiss polytechnic tradition (just consider static graphics)42 with the deconstruction of the avant-gardes.

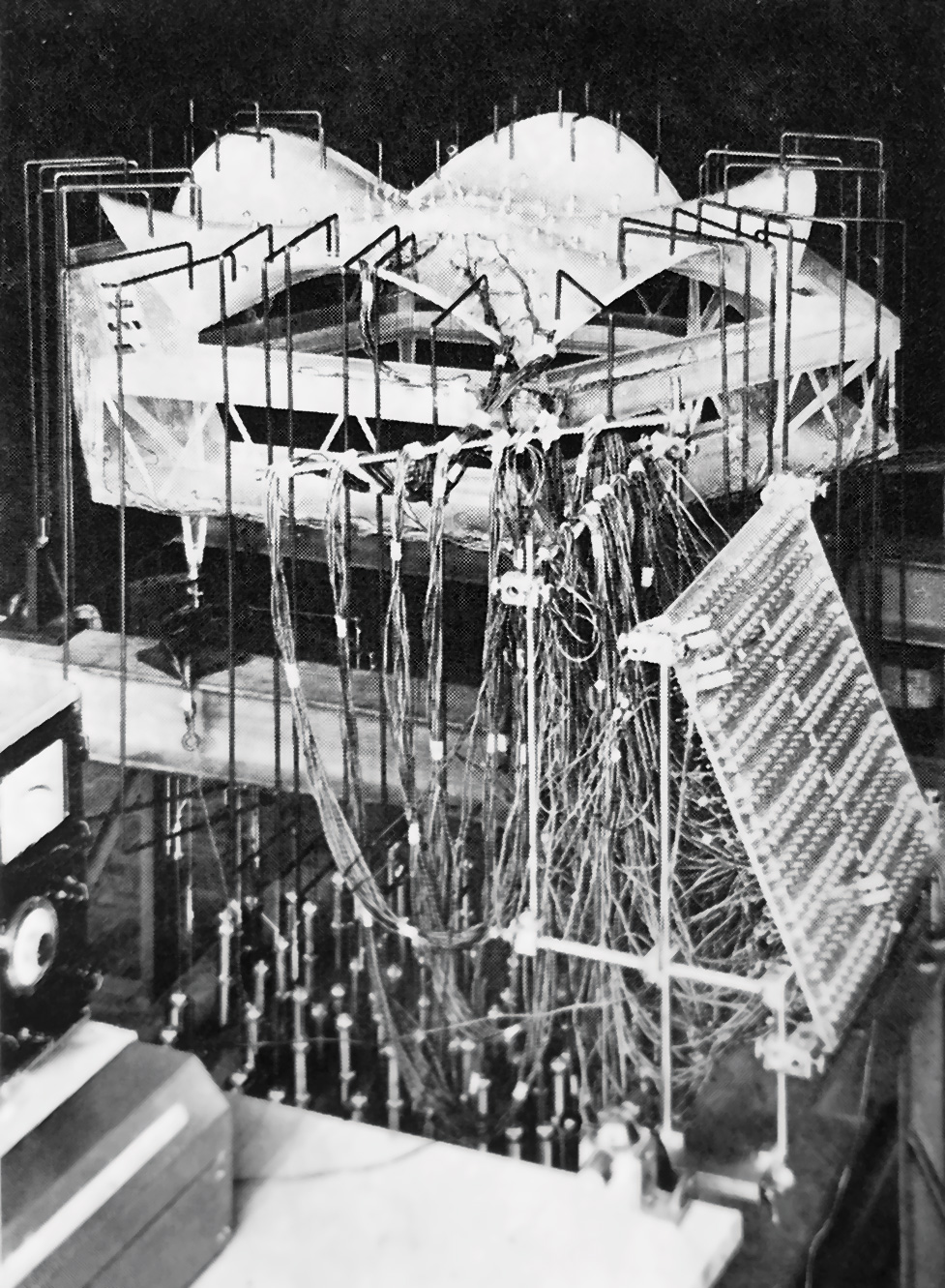

The structural models, nevertheless, are the ones more specifically addressing static experimentation, namely those models created to reproduce, in scale, not only the geometry but also the functioning of a structure. Along the lines of experiences from the same period conducted in Europe and the United States,43 in Switzerland too we find pioneering research, such as that of Heinz Isler (1926-2009) on thin vaults in reinforced concrete,44 conducted since the 1950s by using models made of earth,45 pneumatic devices,46 polyurethane foams and membranes in fabric, capable of suggesting optimized structural forms.

While Isler remained skeptical of the possibility of interaction between physical models and computers,47 the engineer Heinz Hossdorf (1925-2006) grasped its enormous potential.48 He approached trials on the model immediately after taking his degree, in 1953, when he came into contact with the great Spanish engineer Eduardo Torroja, a pioneer of structural modeling.49 In the 1960s Hossdorf tested many of his structures by utilizing models on a smaller scale, and in 1966 he opened his own workshop in Basel, one of the first to use computers to automate experimental processes.50 For Hossdorf, the path to follow was that of hybrid models, in which digital calculation and experimental devices work in symbiosis, compensating for the shortcomings of single approaches.

The models of bridges by Jürg Conzett, made by Lydia Conzett-Gehring,51 are not “structural” ones in the scientific sense of the term, but they are noteworthy, ideally connected to many other reproductions in miniature of this type of infrastructure. Other examples come to mind, such as the models of Swiss bridges by the brothers Johannes (1707-1771) and Hans-Ulrich Grubenmann (1709-1783), exhibited in 2002 in Mendrisio a dialogue with the drawings of John Soane.52 Also for models of structures and infrastructures, then, the meanings and uses are various, and in an ongoing process of updating.

As the cycle of exhibitions Archaeology of the Digital53 has shown, since the 1970s the dialogue between physical and digital models has become increasingly frequent and versatile, also in architecture. Consider, for example the work of Frank Gehry, Coop Himmelb(l)au and Peter Eisenman (just to indicate some well-known names): in all these cases, the relationship between the physical model and the virtual model cannot be interpreted in a unidirectional, hierarchic way, but has to be seen as intertwined, differing on each occasion, with reciprocal effects over the short term and the long term as well.

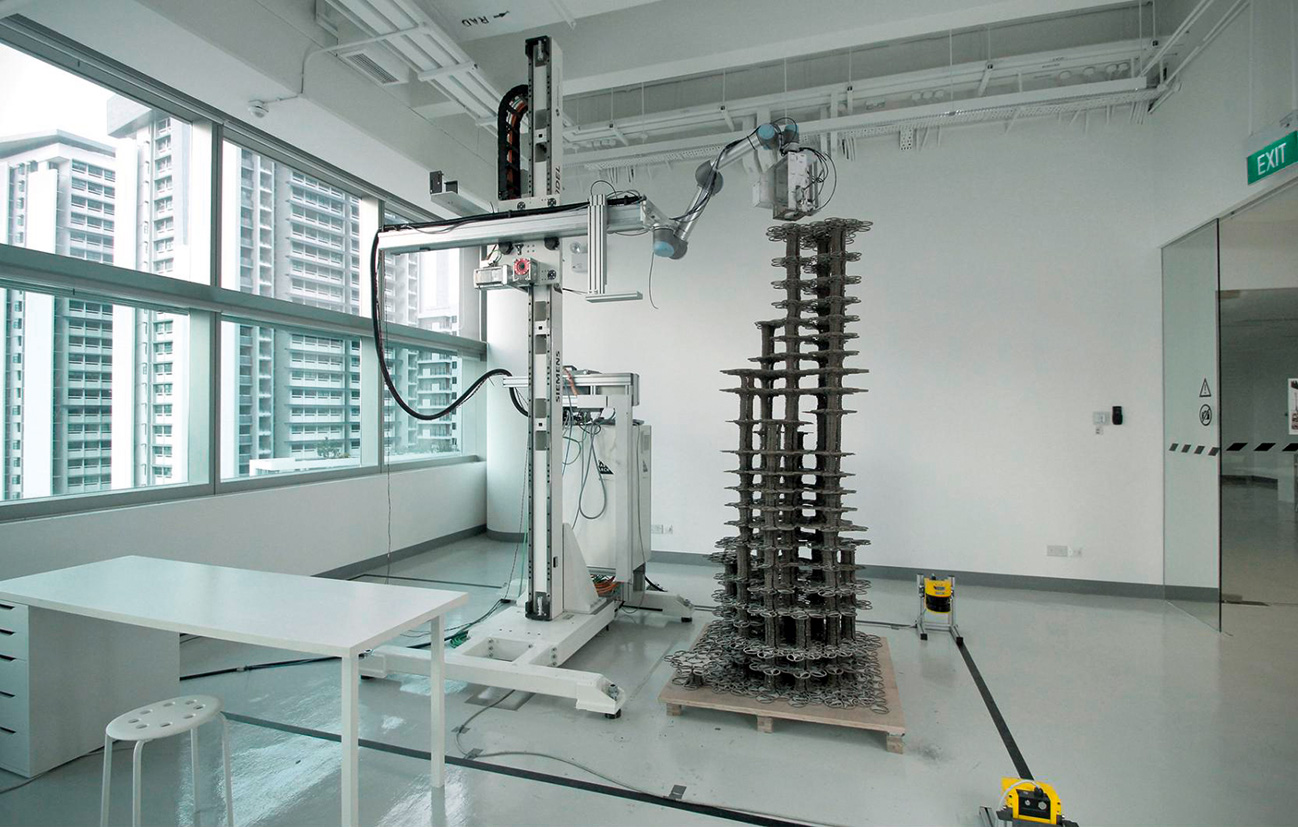

Among the infinite possible takes on this interaction, in recent years in Switzerland the work of Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kohler inside the ETH of Zurich stands out. As we know, their research focuses on processes of 3D printing (“additive digital fabrication techniques used for building non-standardized architectural components”),54 aimed at developing criteria “for a new system of structural logic which can be applied to architecture and that is intrinsic to digital fabrication.”55

Such a process is based to a great extent on the production of models that are quite different from those discussed thus far, namely prototypes on a scale of 1:1 that constitute a “real” proving ground for construction. This pursuit of optimized structural forms is thus linked in various ways to a range of directions of research from the 20th century: from form-finding56 to parametric architecture,57 all the way to the tradition of strength testing of materials, which today take on unprecedented tools and viewpoints.

The boundary between the laboratory and the worksite, in this case, becomes blurry; at the same time, an empirical approach to the Baukunst that is typical of Swiss culture emerges, connected to a traditional vision of architecture based on the pragmatism of the results, the assembly of pieces, the reiteration of construction processes, the study and improvement of the detail, stimulated today by the latest technologies.

Towards a valorization of the culture of the model in Switzerland

There are many other aspects that could be further emphasized. Among them, we can at least mention the role of the model inside Swiss architecture schools. For example, it would be worthwhile to conduct in-depth study of the evolution of the idea and the practice of the maquette at the Academy of Architecture of Mendrisio, where since the school’s founding it has had an important role, setting the character of the teaching and the image of the school, also in opposition to the parallel rise of the digital (and of international schools leaning in that direction). In this case, the “pedagogical” use of the model has been enhanced by the convergence of different visions, brought by teachers from all over the world: from Zumthor (whose “maieutics” through the model represents an exceptional case, later followed by many) to Bijoy Jain, Quintus Miller to Aires Mateus, Riccardo Blumer58 to Anne Holtrop, Burkhalter/Sumi to Adam Caruso,59 etc.

The paths yet to be taken in this research are evidently infinite. But they all seem to converge on one point: the possibility of a valorization of the role of the model inside design culture (and elsewhere) in Switzerland, from territorial planning to engineering, architecture to other areas of design. In this perspective, there are many possible actions, starting from a comparative survey of the models conserved in the archives and collections of various Swiss institutions (museums, universities, professional studios, cantonal archives, etc.). This could serve as the foundation for a campaign of strategic research, in Switzerland and abroad, capable of constructing step by step – model after model – a shared cultural and material heritage, which awaits analysis, protection and valorization as a whole.

Translated by Steve Piccolo

- Cf. F. Gygax, “Das topographische Relief in der Schweiz,” in Wissenschaftliche Mitteilungen des Schweizerischen Alpinen Museums in Bern 6, Bern 1937.

- On these themes, see D. Gugerli, D. Speich, Topografien der Nation: Politik, kartografische Ordnung und Landschaft im 19. Jahrhundert, Chronos Verlag, Zürich 2002.

- A.E. Schubiger, “Das Relief der Urschweiz des Generalleutnants Franz Ludwig Pfyffer von Wyer (1716-1802) und seine Stellung in der Geschichte der Topographie,” in Gesnerus 36, 1979, pp. 74-81; A. Bürgi, “Der Blick auf die Alpen: Franz Ludwig Pfyffers Relief der Urschweiz (1762 bis 1786),” in Cartographica Helvetica 18, 1998, pp. 3-9.

- M. Quaini, “Le forme della Terra,” in Rassegna 32/4, December 1987, pp. 63-73; I. Warmoes, Le musée des Plans-Reliefs, Éditions du Patrimoine-Centre des monuments nationaux, Paris 2019.

- Cf. Colonel Berthaut, Les ingenieurs géographes militaires, 1624-1831, vol. I, Paris 1902, p. 296 et seq.

- M. Cavelti Hammer, “Die Alpen auf Reliefkarten: Prunkstücke von Gyger bis Imhof,” in W. Scharfe (ed.), 8. Kartographiehistorisches Colloquium, Bern 3.-5. Oktober 1996. Vorträge und Berichte, Cartographica Helvetica, Murten 2000, pp. 121-125.

- M. Quaini, “Le forme della Terra,” cit., pp. 69-70.

- 8 We can mention the replica of the relief of Saint-Gotthard Massif excavated in granite (23 tons, 6 x 3 meters) – shown first at the Milan Expo in 2015 and then at the Landesmuseum in Zurich – on which to superimpose virtual contents on geography, demographics, economics, society, etc.

- A.J. Martin, Stadtmodelle, in W. Behringer, B. Roeck (ed.), Das Bild der Stadt in der Neuzeit 1400-1800, C.H. Beck Verlag München 1999, pp. 66-72; B. Roeck, M. Stercken (ed.), Schweizer Städtebilder. Urbane Ikonographien (15.-20. Jahrhundert), Chronos, Zürich 2013. M. Mindrup, The Architectural Model. Histories of the Miniature and the Prototype, the Exemplar and the Muse, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA 2019, pp. 17-18.

- M. Bisping, “Die Stadt im Kleinformat,” in Kunst + Architektur in der Schweiz 4, 2018, pp. 56-65.

- Adi Kälin, “Wenn Zürich wächst, wächst Klein-Zürich stets mit,” in Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 6 November 2019, online: https://www.nzz.ch/zuerich/jedes-haus-das-in-zuerich-gebaut-wird-steht-in-kuerzester-zeit-auch-auf-dem-stadtmodell-ld.1518976?reduced=true.

- F. Nyffenegger, “Schweizvorstellungen zum Mitnehmen. Modellchalets und Chaletmodelle,” in Kunst + Architektur in der Schweiz 4, 2018, pp. 12-21.

- O. Elser, P. Cachola Schmal (ed.), Das Architektur Modell. Werkzeug, Fetish, kleine Utopie, catalogue of the exhibition at Deutsches Architekturmuseum, Dezernat für Kultur und Wissenschaft, Frankfurt am Main (25 May – 16 September 2012), Scheidegger & Spiess, Zürich 2012, p. 341.

- M. Mindrup, The Architectural Model…, cit., p. 236.

- G. Celant, “Il progetto è un oggetto,” in Rassegna 32/4, December 1987 p. 79.

- K.P. Zygas, Form Follows Form: Source Imagery of Constructivist Architecture, 1916–1925 (Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Research Press, 1981, pp. 55-58.

- “Ivan Tschichold, Lipsia: La nuova configurazione,” in ABC – Contributi alla costruzione 2, seconda serie, cit. in J. Gubler (ed.), ABC architettura e avanguardia, Electa, Milano 1983, p. 128.

- Cf. also J. Gubler, Nazionalismo e internazionalismo nell’architettura moderna in Svizzera, Mendrisio Academy Press / Silvana Editoriale, Mendrisio / Cinisello Balsamo 2012.

- Among recent studies on the theme, we can mention the degree thesis of M.A. de la Cova, Maquetas de Le Corbusier. Técnicas, objetos y sujetos, Ed. Universidad de Sevilla, 2016.

- The initial years of Bill’s work are interesting in this sense. Cf. A Thomas, “Max Bill: The Early Years. An Interview,” in The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts19, 1993, pp. 99-119.

- A. von Fürstenberg, P.-A. Croset (ed.), Maquettes d’architectes, catalogue of the exhibition at Centre d’art contemporain, Genève / Le Nouveau Musée, Villeurbanne, Lyon, June-October 1982, Grafis Industrie Grafiche, Bologna 1982.

- The exhibition was held in 1976 but the catalogue was not printed until 1981: K. Frampton, S. Kolbowski (ed.), Idea as Model, Rizzoli International Publications, New York 1981.

- G. Celant, “Il progetto è un oggetto,” cit., p. 86.

- E. Brändle, “P. Märkli & H. Josephsohn,” in M. Mostafavi (ed.), Approximations. The Architecture of Peter Märkli, Architectural Association, London 2002, pp. 54-61.

- R. Sachsse, “Eine Kleine Geschichte der Architektur-Modell-Fotografie,” in O. Elser, P. Cachola Schmal (ed.), Das Architektur Modell, cit., p. 27.

- J. Herzog, in C. Bechtler (ed.), Immagini d’architettura. Architettura d’immagini. Conversazione tra Jacques Herzog e Jeff Wall, Postmedia Books, Milano 2005, p. 11.

- Ibid. 27.

- J. Herzog interviewed by T. Vischer, in Herzog & de Meuron, Wiese, Basel 1989, p. 51.

- Cf. Herzog & de Meuron, Architektur Denkform, 1988. Cf. also J. Herzog interviewed by T. Vischer, in Herzog & de Meuron, cit., p. 52

- P. Ursprung, “Exponierte Experimente. Die Modelle von Herzog & de Meuron,” in O. Elser, P. Cachola Schmal (ed.), Das Architektur Modell, cit., p. 52.

- M. Mindrup, The Architectural Model, cit., pp. 158-160.

- R. Zaugg, Herzog & de Meuron, Herzog & de Meuron. Eine Austellung, Cantz, Ostfildern-Ruit 1996.

- J.-L. Cohen, “Models and the Exhibition of Architecture,” in K. Feireiss (ed.), The Art of Architecture Exhibitions, NAi Publishers, Rotterdam 2001), pp. 25-33.

- P. Ursprung (ed.), Herzog & de Meuron: Natural History, catalogue of the exhibition Herzog & de Meuron: Archaeology of the Mind at CCA Montréal (23 October 2002 – 6 April 2003), Lars Müller, Baden 2002.

- P. Ursprung, Exponierte Experimente, cit., pp. 52-53.

- D. Sudjic, “Laboratory and Cabinet of Curiosities. The Archive of Herzog & de Meuron in Basel,” in Werk 4, 2015, online version: https://www.wbw.ch/en/magazine/reports/original-texts/2015-4-laboratory-and-cabinet-of-curiosities.html

- See, for example: M. Berteloot, V. Patteeuw, “Form / Formless. Peter Zumthor’s Models,” in OASE 91, 2013, pp. 83-92; “Peter Zumthor. Kolumba,” in O. Elser, P. Cachola Schmal (ed.), Das Architektur Modell, cit., pp. 237-240.

- In 2012 the Kunsthal of Bregenz presented a large series of models, while in 2018 the Venice Biennale featured the installation Dreams and Promises. Models of Atelier Peter Zumthor.

- Cf. Vitruvius, De architectura, Book X, Leon Battista Alberti, De re ædificatoria, 1450, Book II, chap. 2, V. Scamozzi, L’idea della architettura universale, Venezia, 1615, Book I chap. 15.

- E. Viray, C. Kerez, “Uncertain Certainty, Certain Uncertainty,” in C. Kerez, Uncertain Certainty, Toto, Tokyo 2013, p. 270.

- Ivi, pp. 22-31.

- B. Maurer, Karl Culmann und die graphische Statik, Verlag für die Geschichte des Naturwissenschaften und Technik, Stuttgart 1998.

- G. Neri, Capolavori in miniatura. Pier Luigi Nervi e la modellazione strutturale, Mendrisio Academy Press / Silvana Editoriale, Mendrisio – Cinisello Balsamo 2014; B. Addis (ed.), Physical Models. Their historical and current use in civil and building engineering design, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin 2021.

- Cf. J. Chilton, “Heinz Isler and his use of physical models,” in B. Addis (ed.), Physical Models, cit., pp. 613-637.

- Cf. H. Isler, “New Shapes for Shells,” in Bulletin of the International Association for Shell Structures 8, 1961; Id. “New Shapes for Shells – Twenty Years After”, in Bulletin of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures 71/72, 1980, pp. 9-26.

- Cf. E. Ramm, “Heinz Isler – The Priority of Form,” in Journal of the International Association for Shell and Spatial Structures, vol. 52, no. 3, September 2011, p. 147.

- Ivi, p. 151.

- Cf. P. Cassinello, “Heinz Hossdorf: his contribution to the development of physical model testing,” in B. Addis (ed.), Physical Models, cit., pp. 551-567; H. Hossdorf, Heinz Hossdorf. Das Erlebnis Ingenieur zu sein, Birkhäuser, Berlin 2003.

- J. Atuña, “Eduardo Torroja and his use of models from 1939,” in B. Addis (ed.), Physical Models, cit., pp. 477-510; G. Neri, Capolavori in miniatura, cit., chap. I.

- H. Hossdorf, Modellstatik, Bauverlag GMBH, Wiesbaden und Berlin 1971.

- Shown recently in Mendrisio in the exhibition Landscape and Structures held at the Teatro dell’architettura of Mendrisio from 12 April to 7 July 2019.

- A. Maggi, N. Navone (ed.), John Soane e i ponti in legno svizzeri: architettura e cultura tecnica da Palladio ai Grubenmann, Accademia di architettura, USI / Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio, Mendrisio - Vicenza 2002.

- G. Lynn (ed.), Archeology of the Digital, catalogue of the exhibition at CCA Montréal (7 May – 13 October 2013), Canadian Centre for Architecture, Montreal 2013.

- Website of Gramazio Kohler, visited on 14 September 2020.

- Ivi.

- S. Hildebrand, E. Bergmann (ed.), Form-finding, form-shaping, designing architecture: experimental, aesthetical, and ethical approaches to form in recent and postwar architecture, Mendrisio Academy Press, Mendrisio 2015.

- I.R.M.O.U., Mostra di architettura parametrica e di ricerca matematica e operativa nell'urbanistica, catalogue of the exhibition at the Milan Triennale (September-October 1960), Arti grafiche Crespi, Milano 1960.

- G. Neri (ed.), Sette architetture automatiche e altri esercizi, Mendrisio Academy Press, Mendrisio 2018.

- H. Teerds, J. Floris, “On Models and Images. An Interview with Adam Caruso,” OASE 84, 2011, pp. 128-137.