Architecture Now: New York, New Publics

MoMA new exhibition on the local New York scene

Last February, MoMA inaugurated a major exhibition on the local New York scene, with a dozen projects showing the extent to which environmental and social issues are forging a new generation of architects. The United States was thought to be incurable, but here it is on the virtuous path of reuse, consultation and, more broadly, of architecture with a high social and ecological added value. Espazium spoke to Evangelos Kotsioris, an Assistant Curator and co-curator of the exhibition (along with Martino Stierli, Chief Curator, and Paula Vilaplana de Miguel, Curatorial Assistant) organized by MoMA’s Department of Architecture and Design.

Evangelos Kotsioris: The exhibition “New York, New Publics” is part of a new series that we call 'Architecture Now'. It’s a 3-year cycle recurring platform to showcase contemporary architecture, groundbreaking ideas that can have an impact on the design disciplines at large. Here in New York, like elsewhere, during the pandemic, there was a big discussion about how we could coexist outdoors in shared spaces. The design of everyday life became the object of reflection and subject of redesign. Simultaneously, there was a wave of new scholarly studies and discourses on the public aspect of architecture, and new types of commons. These two things seemed to come together and coincide with the wave of social movements that emerged shortly before and during the pandemic around racial inequality and broader social justice. It became clear that it was not possible to ignore all this fermentation and cross-polination that was taking place, and in particular how it was affecting the practices of young architects in the city who were seeking to establish their place and position at the time. So, the idea of both New York as a site of focus and that of the « public » aspects of architecture came up very naturally. We then emphasized the plural in the title. “Public” a noun and an adjective. Thus, “publics” here refers not only to the ideas of public architecture, or the notion of architecture as a public concern, but also the multiplicity of publics for which the built environment can serve as a shared amenity. We wanted to address a multiplicity of approaches; how can architecture be public today? The twelve projects in the exhibition all interpret and answer this question in a different way, ranging from the very practical to the more metaphorical. All together they paint a kind of landscape of this moment in time, the architecture of the here and now.

Espazium: How does the American way of life become sustainable? The exhibition gives some examples. But how can one go beyond "good intentions"? How do we deal with the main components of the American city (suburban housing, car-oriented planning) that are completely unsustainable?

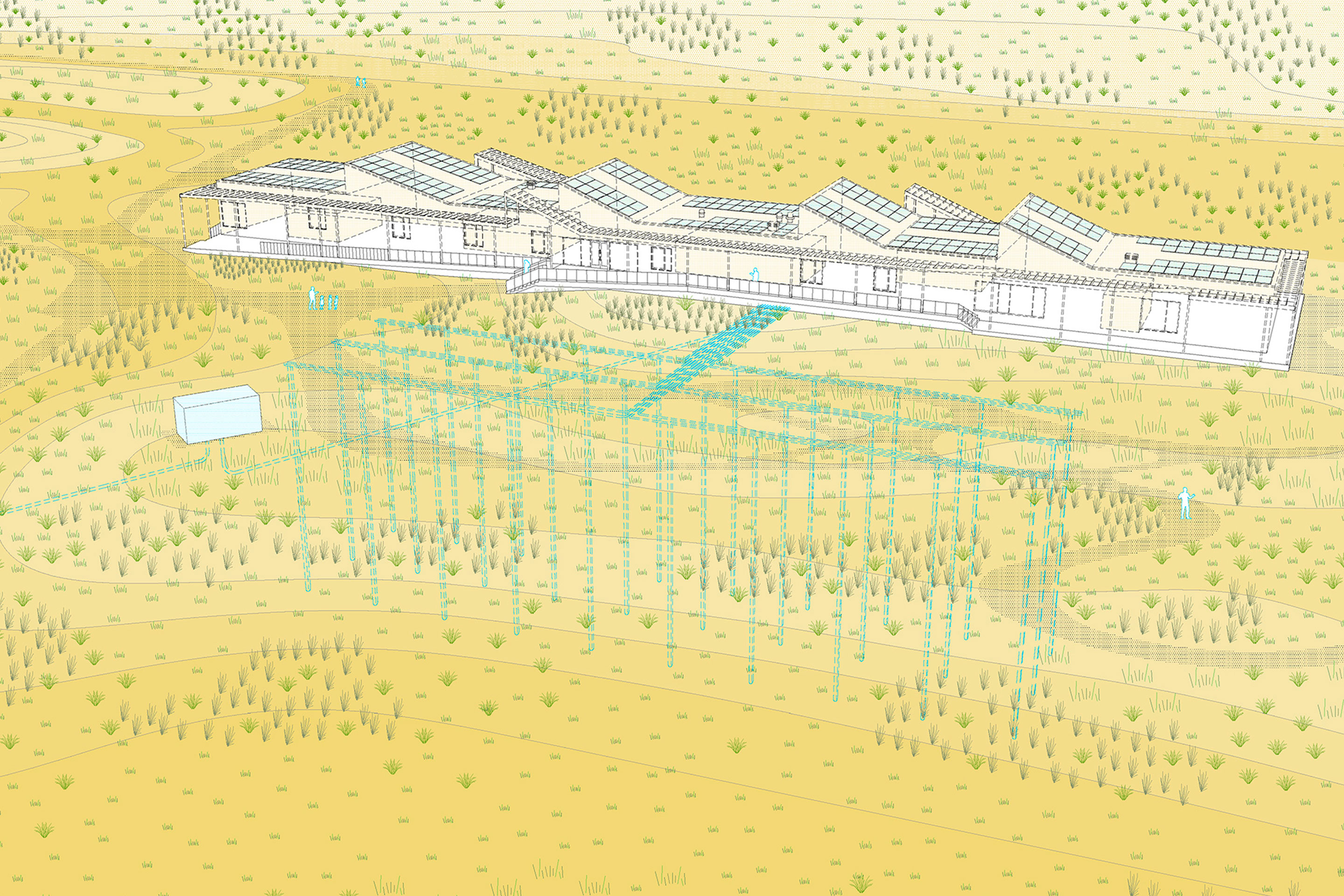

There is obviously a much larger discussion about how to remedy the urban legacies of the 20th century. Today, this questioning comes at a time when civic infrastructure across American cities have aged simultaneously and needs to be either demolished, replaced or carefully restored. Most of the young architects in the exhibition start from the need to consider new answers to this challenge. They explore a different mode of production for architecture that critically engages with what is already there. One could say that they are breaking with the old heroic figure of the architect who actively sought to replace the old with the new. During the post-WWII period, modern approaches to urban renewal were often communicated through the invasive medical metaphor of “surgically” removing the “cancerous” parts of the city and replacing them with “healthy” tissue. Many of the young architects featured in this exhibition are more interested in the potential, and even beauty, of the already existing. They will build on it, multiply it, resize it and sometimes even poetically reimagine it rather than remove it in order to propose something completely different. This is an important generational change that is emerging from many projects, such as Only If's New Public Pool, which proposes a series of small-scale interventions that can extend the use of New York’s network of more than 64 pools throughout the year.

As far as the CO Adaptive’s Timber Adaptive Reuse Theater is concerned, the project seems to be the result of a very sensitive, cautious and incremental approach. I am wondering if this project is representative with the reality of wood construction in North America and the fact that even today, wood is the material of which most American homes are made. Isn't this project too European-oriented, and therefore less representative of the American reality in regard to wood?

I should perhaps start by saying that New York City is not representative of the United States as a whole. As far as wood is concerned, if the use of timber frame structure is indeed quite developed across the country, here in New York structural steel became particularly popular in the beginning of the 20th century, even for smaller structures. The project you mention by CO Adaptive is an adaptive reuse of an old industrial foundry in the Gowanus neighborhood of Brooklyn and had been built around 1890. Erected before the wide use of steel, its primary structure was made of longleaf pine, an extremely strong type of wood that was used in large structures of this type. In fact, it was considered the strongest structural material before structural steel and is found, covered up, in many buildings in the city. What links the materiality of this project specifically to the history of the United States is the fact that longleaf pine is a tree species native to the Southeastern part of the country, as it was logged often on publicly-owned land in Virginia, Florida, or Texas, and then transported to urban centers, like New York on log trains. Beyond making this remarkable structure once again visible, CO Adaptive have also complemented the existing structure with new CLT elements constructed out of ethically logged wood. In fact, this is the first commercial building in New York to use CLT for its structure. For this reason, the project has an educational dimension for other generations of architects who have been very skeptical about the use of CLT and think that it is only suitable for smaller structures or interior renovation: This project helps to show the potential and to dispel some of this mistrust.

Regarding the participatory renovation for the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), is empowerment compatible with public housing? Can refurbishment provide empowerment? How do we deal with the fact that the inhabitant, in the position of a tenant, does not generally decide on their environment?

The way Peterson Rich Office (PRO) worked on this project, what they call a repertoire of “scalable solutions,” rather than a single “one size fits all” kind of design, is particularly innovating. While the project was initiated by the architects through as part of a research fellowship, it has evolved into anactual collaboration with NYCHA. Currently, this collaboration has involved their active engagement with 16 different public housing campuses, the proposed directive for which have been based on more than 100 community meetings with local inhabitants. PRO developed a new method to learn and understand what actual residents would like to see changed on their compounds. This effort included the development of a board game that allows for simultaneous discussion, planning and play. In many ways they are using already known participatory design methods, but which have been rarely used in New York City’s public housing. What is interesting is the diversity of proposals that emerged from one site to another. They range from the very technical to the more social, from updating elevators and HVAC equipment to providing social spaces for gathering, and that's what makes this project truly unique. It is a genuine bottom-up planning and design that consists of a kit of parts that can be incrementally redeployed according to the wishes of a particular group. This is important because this type of social housing from the urban renewal period was always seen literarily from an aerial perspective. Planners and architects would draw an outline on a map and dictate how to replace huge pieces of urban fabric with little to no input from those immediately affected. This project is much more from the perspective of the ground. It takes a lot longer and it's a lot harder to reconcile all these different inputs desires. But in doing so it creates much more responsive projects that can be adopted and improve the lives of 1 in 16 New Yorkers who live on NYCHA’s campuses today.

Community-oriented design is something that avant-garde architectural practices in the United States are finally managing to address in a more relevant way. As opposed to sustainability, which is more often iconic. Does this mean that change will more probably come from this perspective?

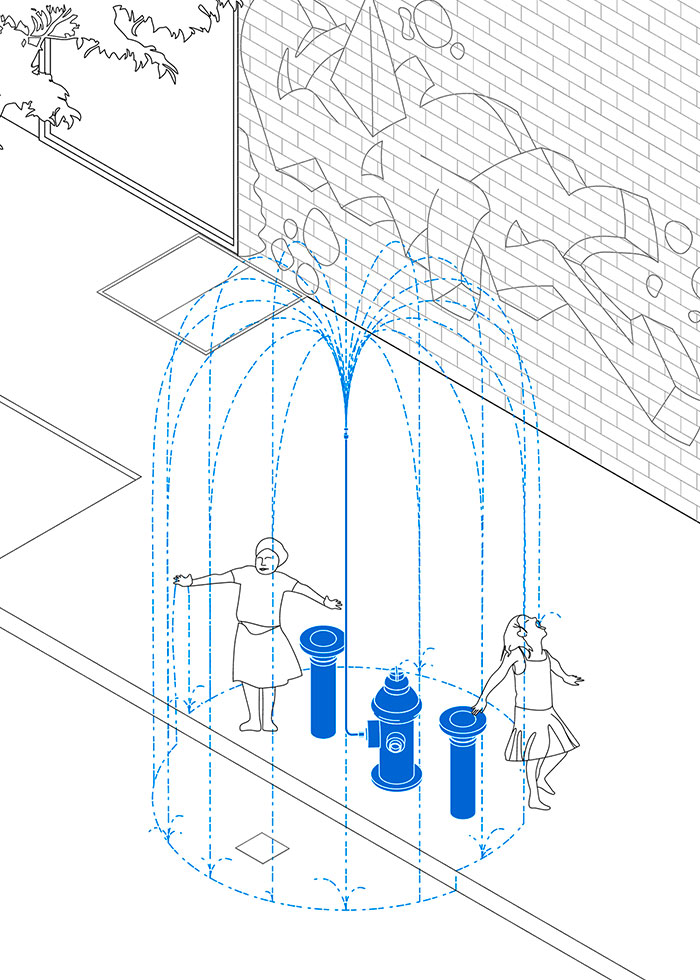

I would argue that there have always been examples of community-oriented practices, but perhaps the tools to share information and learn from each other have brought about the largest change of minds and practices. Social media, for instance, has radically altered the way we hear and hopefully pay attention and care for the opinions of others. Many young designers and architects currently working in the city have wanted to engage in projects that have a social dimension, that relates to the city and its communities. Unfortunately, there is little space for this kind of work to happen, let alone be acknowledged. There are very few competitions for public-oriented work and housing is still mainly produced by large-scale, private developers. In the absence of a framework that can allow this kind of publicly-facing work, many designers are initiating projects to simply create that space where engagement with local communities and neighborhoods can be made possible. There is a renewed interest in this approach, which had a brief “golden period” in New York during the early 1970s, when small-scale public infrastructure was commissioned to some of the best architects in the country. This idea of architecture enabling people’s “right to the city” is thankfully making a comeback, imbued with a renewed ambition and pragmatism, expressing a novel understanding of what the figure of the architect can and should contribute to civic life. In projects, like TestBeds by New Affiliates and Samuel Stuart-Halevy or the New Public Hydrant by Agency–Agency and Chris Woebken Studio, the architect plays much more the role of a matchmaker, or the inventor of an open-source design system, rather than the creator of a signature “napkin sketch”. I think that some of these attitudes will become part of the profession, the discipline and the practice, rather than something that will be remembered as having happened around 2023. Our aspiration is that putting some of these commendable initiatives on display through MoMA can render visible the value that design, and architecture can add to the shared spaces of the city. It’s a way of acknowledging these efforts, and hoping other practices will follow suit.

Architecture Now: New York, New Publics

February 19, 2023 – July 29, 2023