On the tectonics of detail

Interview with Eduardo Souto de Moura

In the first of three interviews in Archi 01, Eduardo Souto de Moura talks about his position as an architect and thinker, in relation to the building tradition and the new perspectives of the profession.

Per la versione italiana cliccare qui.

Carlo Nozza: Since Archi reaches an audience of both architects and engineers, I would like to start this conversation by asking you how you collaborate with different consultants and thus integrate components and technological specialities into your work process and, ultimately, into the architectural result?

Eduardo Souto de Moura: Architecture cannot exist without engineering. In earlier times, when architects did not speak Latin, engineers were not necessary. But once architects adopted Latin, it became essential to have someone by their side who also spoke the language, engineers. When I start drawing the first sketches of a project, I immediately call an engineer, Jorge da Silva or Rui Furtado, to get their opinion. I very quickly visualise the materiality; engineers clear their minds of everything that is not construction. While the architects are lingering on the narrative on issues of the environment, ecology, energy, sociology and typology, the engineer does a tabula rasa with his exclusive interpretation of stability. This is why having an engineer involved from day one is crucial. For instance, in my current design for a TGV station—a contemporary reinterpretation of a Roman aqueduct—the engineer’s input is indispensable. It is no longer the old ideas of the XIX century, which are often empirical or based on simple common sense, but today collaboration with engineers is essential, as is dialogue with the client.

CN: What is the relationship between tradition and innovation in your projects? For example, referring to the TGV project you have just mentioned, how do you transform the spatial consistency of a Roman aqueduct into a contemporary work?

ESdM: I work through images. While I value theoretical discourse for providing substance and awareness to action, it doesn’t inform me about architecture itself, only about my position as a citizen in relation to society. Architecture, first and foremost, is a service. When a client asks me to design a TGV station in Gaia, it raises a social question. But my next step is always to ask: why are we doing this, and for whom? The goal is to provide the best service while using the least resources.

CN: More specifically, how do you develop research to innovate building systems in your architectures?

ESdM: That is what interests me. My vision of architecture has no narrative. There may be one that interests me, but starting with a narrative would only lead to disaster. Architecture justifies and motivates itself: a pillar is a pillar, a beam is a beam, a pillar combined with a beam can produce a construction, and a construction can produce different results. I have to make an almost schizophrenic effort to imagine that the whole world is contained in an A4 sheet of paper, reducing the project to its simplest set of problems to solve. Otherwise, I can’t move forward. It might sound extreme, but that’s how it is. Too often, architects spend a lot of time talking without reaching any concrete conclusions.

CN: Since your Erasmus experience here at FAUP in Porto, I have seen that the extraordinary quality of certain Portuguese architecture is also the result of the cultural references and tools with which you have been trained. What were your references? Which tools do you prefer to use?

ESdM: The tools I use are the traditional ones I was educated with. The period I spent at the School of Architecture was very brief because it coincided with the Carnation Revolution, during which the school was basically closed for long periods. At that time we were working from a very political and social approach, based on the sociological and anthropological debate around the design of housing for the underprivileged classes in the city of Porto. I worked on SAL (Serviço Ambulatório de Apoio Local) projects, primarily dealing with the social dimension of architecture, which reinforced my understanding of architecture as a service. However, this was not enough. While exploring new solutions to transform reality, the Minister of Housing Policy, who was also an architect, evaluated the projects we had prepared as students and selected the most promising ones for funding and implementation.

Together with Adalberto (Dias), Manuela (Sambade), and Teresa (Fonseca), we engaged in discussions on semiology and dialectical materialism at school. Yet we were not able to make projects that could be built, so we had to look for an architect and we went to the best one, Alvaro Siza. When Siza agreed to help us, it marked the beginning of my enduring connection with him, after all he was my real school.

We are from different generations, Siza mentions that he is not particularly interested in structure, he never shows columns and beams, his architecture has a skeleton, as if it were a sculpture, which he then covers and clads with different materials. I do the opposite – I had never thought about it – for me the structure is the foundation of architecture, it is its expression, which is then completed to protect the interior space, it is the principle of temples. In my view, the basis of architecture is the column, from the Doric and then the Ionic to the steel column in the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

CN: Today we are in the midst of an extraordinary transformation of work processes Do you think digital tools can help the architectural design process?

ESdM: Of course they help. To say otherwise would mean opposing progress. However, I firmly believe they are never the only solution. It is natural to become very radical when something emerges people often predict the end of everything, just as they did when computers first appeared. That is why I am not against digital tools, just as I am in favour of artificial intelligence, because it allows us to manage data and information more effectively, to avoid the arbitrary solutions that Rafael Moneo warns us about. On the contrary, when used wisely, artificial intelligence can guide us toward the most appropriate solution for the service we aim to provide.

CN: In the years during which I have collaborated here in your studio in Rua do Aleixo, I had the chance to appreciate the constant and obstinate attention you pay to the context in which you are going to intervene. For example, I remember the studies of the theatre of Epidaurus to find the best location in the landscape, or the conversations with engineers to understand the construction of hydroelectric dams along the Douro river and to understand the proportions of the structure at the scale of the landscape, to design the stadium of Braga. In general, when you start a project, how do you interpret the place and how do you confront the local natural, environmental, cultural, technological and economic reality?

ESdM: I try to help. I must have said in the past that God made the world badly. He rested on Saturday leaving plenty for us to finish. People need to be able to cross rivers without getting their feet wet, to sleep without being drenched by rain. A Brazilian writer (Clarice Lispector) said that the world consists of what God made, which we call nature, and what man made, which we call architecture and engineering. I am not religious, but I believe every place has its own energy—positive or negative—though I don’t mean this superstitiously.

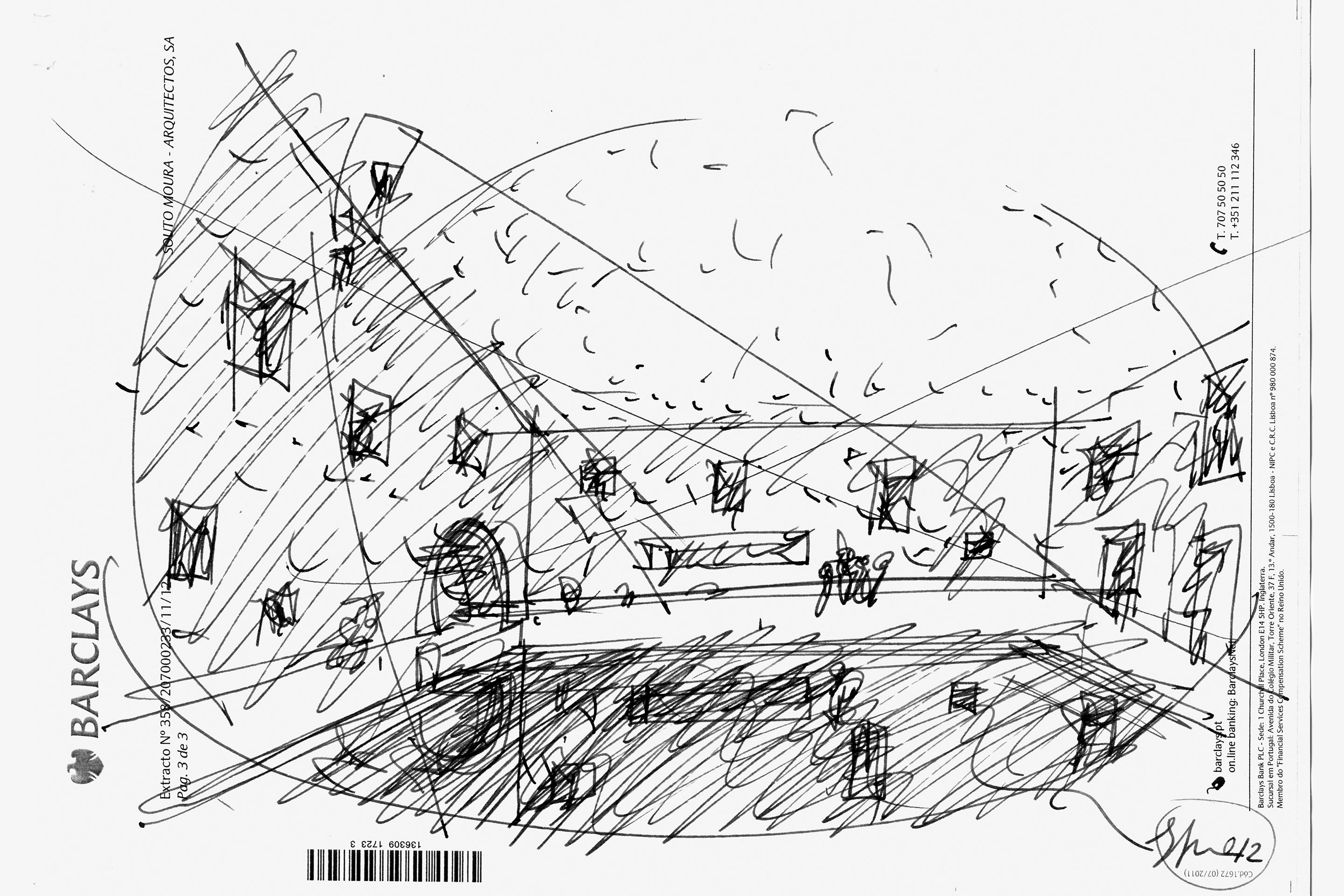

When I am asked to work on a project, it is because someone feels that something is missing, so I make a proposal to complete the existing. This happened, for example, with the stadium in Braga, you remember I was criticised at the time because we were digging up the mountain for someone and destroying it, after it was built I went back to see it and from a distance, covering it with one hand, I said to myself that everything was fine as usual, but when I discovered it I said to myself that the landscape had actually improved. To design is to make objective analyses of what is missing, but these are not very useful on their own, so you need to visualise through sketches, which for me are unconscious analyses, a proposal that complements what exists. Sketching is immediate and allows you to determine whether a round or pointed architecture, or whatever else, might work. It immediately generates a dialogue, a discourse that enables you to come to conclusions through a quick exchange, and that for me is research.

One of the most important texts in modern architecture, in my opinion, is the lecture that Rafael Moneo gives on arbitrary architecture for the entrance to the Royal Academy of Spain. He says that architecture always begins arbitrarily, a person arrives at a place, sits down and begins an analysis, which is made through a series of sketches made in rapid succession, as if they were a flash. Herberto Helder also explains this well in the books «Flash and Photomaton & Vox». Through sounds or images we quickly learn the place and then visualise, through further sketches, which are unconscious analyses, solutions dictated by intuition. Some say intuition has no rational basis, and others, like certain philosophers. For me intuition is very important because it is an instantaneous decision that is the comes from knowledge acquired over many years.

So, the choice of intuition is not arbitrary, but very personal. The project is the process of researching, analysing and synthesising the reasons why it is not arbitrary. The construction must be rational, otherwise it collapses.

CN: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development launched by the United Nations in 2015, the New European Bauhaus proposed by the European Union in 2021, and the Baukultur Strategy being implemented in the Swiss Confederation generally promote sustainable approaches to design, where do you stand on these issues?

ESdM: History is filled with buildings that would not meet, in my opinion, the distorted and technicist demands of what is now considered ecological or sustainable.

Are the Parthenon, the Pyramids, the Pantheon not sustainable? What about Villa Savoye or Fransworth House? My question is this: is sustainability just a mechanistic yes/no answer to technical questions, or is it the result of a relationship, a balance with the environment?

In my opinion, the concept of sustainability needs to be rethought. Architecture is not art, though it can become art, its goal is beauty, and this is not abstract, but related to well-being of a place. Villa Savoye is a monument to thermal bridging, but it is also architectural history.

I understand the need to focus on sustainability to preserve our planet, but it is also clear that one should not be extremist, as some technical protocols or political groups might suggest. Furthermore, the design of the different specialities today takes too much autonomy, it is urgent that people restore the idea of the interconnection between all the different aspects of architecture. Nowadays, urban planners focus only on roads, architects on façades, and structural engineers on keeping the building from falling down. We are losing a European humanistic tradition that has its roots in ancient Greece, continues through the Roman era, Humanism, the Renaissance, Baroque and Modernism, which is another Renaissance built of steel and reinforced concrete.

I think we are witnessing the exaggerations that are typical of beginners, often accompanied by speculation;in my opinion, Baukunst should simply represent the minimum condition for building.

CN: Today, sustainable design also means planning the maintenance of buildings over time. What is your opinion on this?

ESdM: There is no culture of maintenance in Portugal. Maintenance is a luxury of wealthy countries, in this country it is already a celebration to be able to build, and at the budgeting stage the work to be done are halved because the architect’s designs are often deemed too expensive. So you don’t see the problem in the long term.

CN: As you know, I maintain a close and continuous relationship with the cultural and particularly architectural reality in Portugal. While the desire to innovate design processes is very clear to me among the new generations of architects, I agree with you that the common and widespread sensitivity on sustainability issues is still too often superficial or poorly informed here, as in most of Europe, including Switzerland. The duty to be responsible is not a new fact, in fact it runs through the history of construction over the centuries, so don’t you think that we as architects should push harder to spread this message among people?

ESdM: Yes, I think it should be pushed more. In fact I know of some interesting cases like Siza’s works in Holland, where the skirting boards are made from glued cork to save money, which is then invested in the joint between the brick walls and the windows, areas where moisture can seep in. Here the joint is sealed with lead. So in these projects a lot of money was spent on sealing the envelope, while money was saved on the skirting boards. I also had some experience abroad, for example in Switzerland with the Novartis building or with Siza in other projects, and I acted accordingly, but in Portugal it is not yet possible because it is still considered too costly.

CN: I remember a lecture of yours in Serralves many years ago during which, talking about Santa Maria do Bouro, you said that throughout history there has been a tradition that old buildings were often dismantled and the materials reused to construct new ones. What is your opinion on the reuse of materials and elements from the demolition of ordinary buildings?

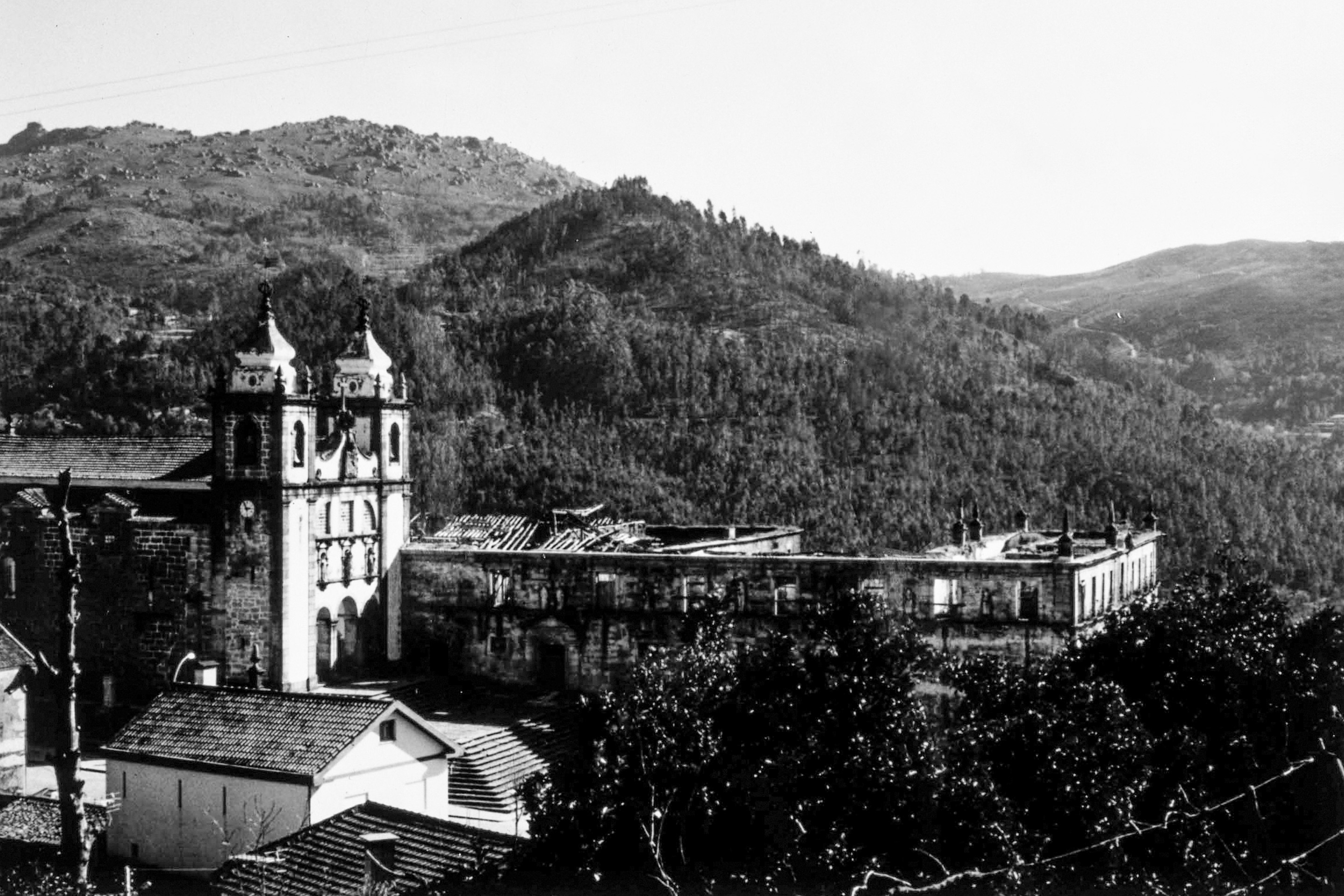

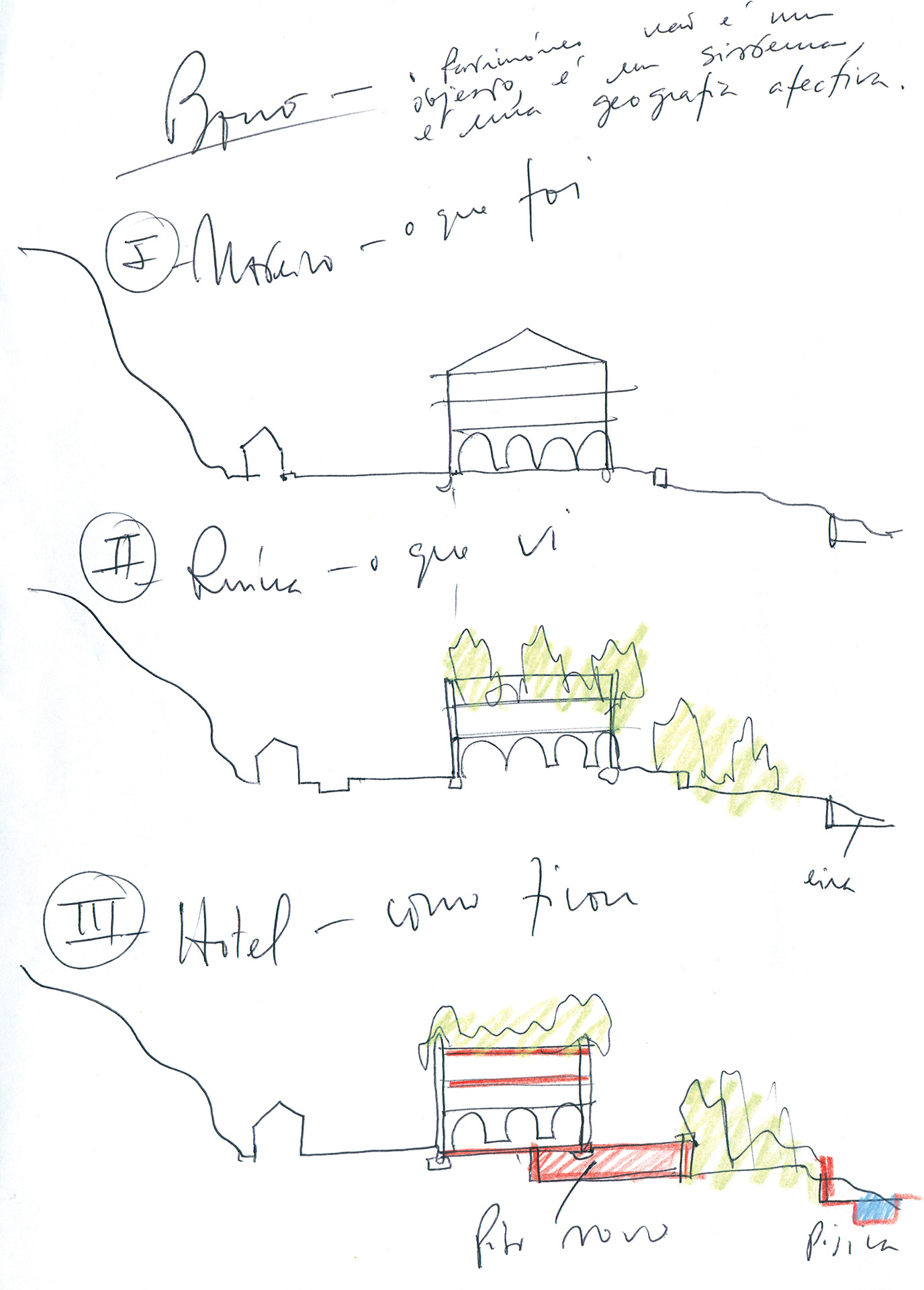

ESdM: The first step is to carry out a serious economic study. If the building has quality it should be maintained and reused, if not it can be replaced, unless it is not a particularly valuable and historic building. For example, I’ve worked on interventions in three monasteries that are part of Portuguese Heritage, the Convent of Santa Maria in Bouro, the Convent of the Bernardas in Tavira and the Monastery of Alcobaça, adopting three different approaches.

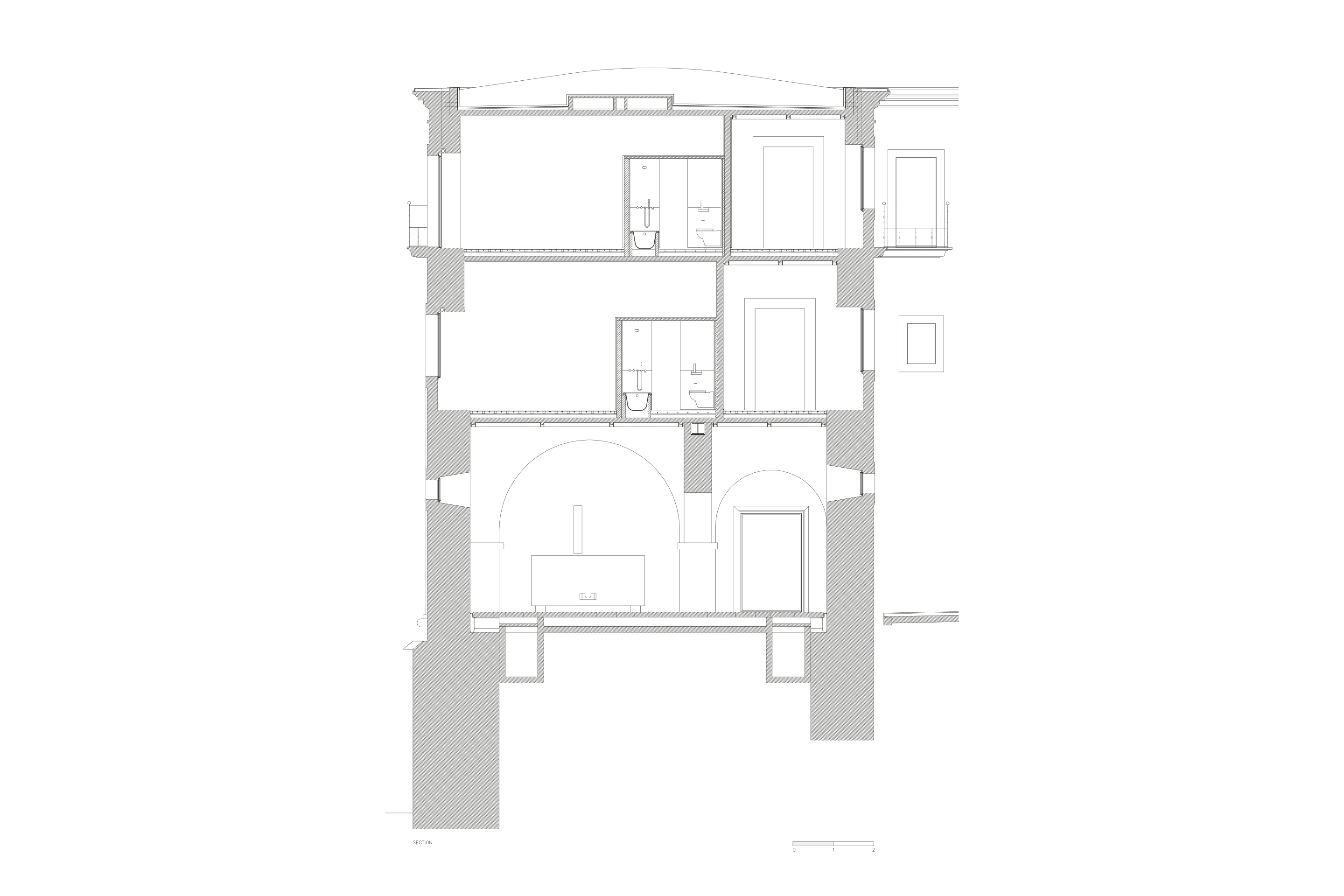

The intervention in Bouro was more radical and aligned with the principles of the Venice Charter: what is old remains original, what is new is recognizable, in short, an anti-pastiche attitude. It is a modern work realised with ancient stones. At the Convent of the Bernardas, I preserved the type and form of the original building, which had already been modified over time. Initially it was a monastery, then a flour factory, therefore I reinforced this image by adding a chimney, which is not a sculpture but is connected to the heating boilers, and then a roof, as well as opening 110 windows to meet the needs of the change of use, from a factory to a residential building. This project tells of the constant evolution of an architecture without the use of striking or manifest works. In the Alcobaça monastery, after having intervened in a very important way in Bouro and Tavira, I experimented a third, less intrusive approach, accepting, with some difficulty, the imperfections of the existing building, like a grandmother who, not being perfect, shows her age with dignity and therefore does not dress in leather, but in a suit that shows her serenity. In Alcobaça, what was crooked has remained so. The client is private, the furniture is minimal, the corridors are completely empty, and it contains only furniture designed by me and Siza, which will become an investment over time. It is therefore a very gentlest approach, all the wrinkles left by time are visible. Of the three interventions, it is the one where the architect’s intervention is the least visible.

So I think there is no one way to intervene in heritage, you have to use common sense and decide from time to time how to proceed.

CN: During the design process, when and how do you choose which material to use, the resulting construction system and finally visualise the architectural result?

ESdM: It depends on different factors. In general, I consider the triangle with material, building system and language at the vertices to be almost sacred, and I rarely make exceptions. It is a reference that goes with me.

CN: I am thinking for example of how Mies van der Rohe or Louis Kahn treated this relationship between structural concept and architectural result.

ESdM: Mies van der Rohe is fundamentally objective in structure, which he masters superbly, and is formalist only in the corners. The story is full of betrayals, but it is not the story of adulterers that is interesting, but Flaubert’s Madame Bovary. It is a philosophical discussion about how truth is not always beautiful, otherwise there would be no literature. Mies invented false corners or added unnecessary profiles just to enhance the verticality of the buildings, but even in these cases he never hid the fiction, which he used instead as if it were make-up for a lady, used to enhance the beauty. Louis Kahn, on the other hand, is one of the architects I draw from least, because I do not think these structures are very real. I’ve been to India, Pakistan and Bangladesh: the bricks are often broken, and I know there have been endless discussions with the engineer because the concrete elements don’t work the way they should. Kahn, unlike Mies, hid the fiction.

For me, structure is essential to understanding architecture. This is why I find the structuralist movement intriguing; it brought a degree of rigor to the humanities, which had previously been too subjective and, at times, arbitrary.

CN: Your architecture is representative of an ancient knowledge, always aimed at innovation. How do you choose the materials to realise your works?

ESdM: I believe in pictorial architecture. When I build a stone wall it is not out of nostalgia or an attempt to revitalize the old construction, but because I like stone and it is pictorial.

I realized this when I was preparing the speech for the Pritzker Prize: my architecture is modern, but it does not break with tradition. When I build I start with a concrete wall, because stone has various imperfections to be used directly in architecture, and then I cover it in stone. It has a lot to do with what Shinkel thought or with John Soane’s house in London, with the idea of a collecting and pictorial interest of the past.

That is why I still fear designing windows so much, I can replicate the precise measurements in height and width of an antique window that I admire, but today I would lose the depth, because where a 60 cm deep stone was used, I would have to use a 15 cm block, 20 cm maximum.

CN: Are you interested in innovative materials?

ESdM: I am waiting to be able to use carbon...

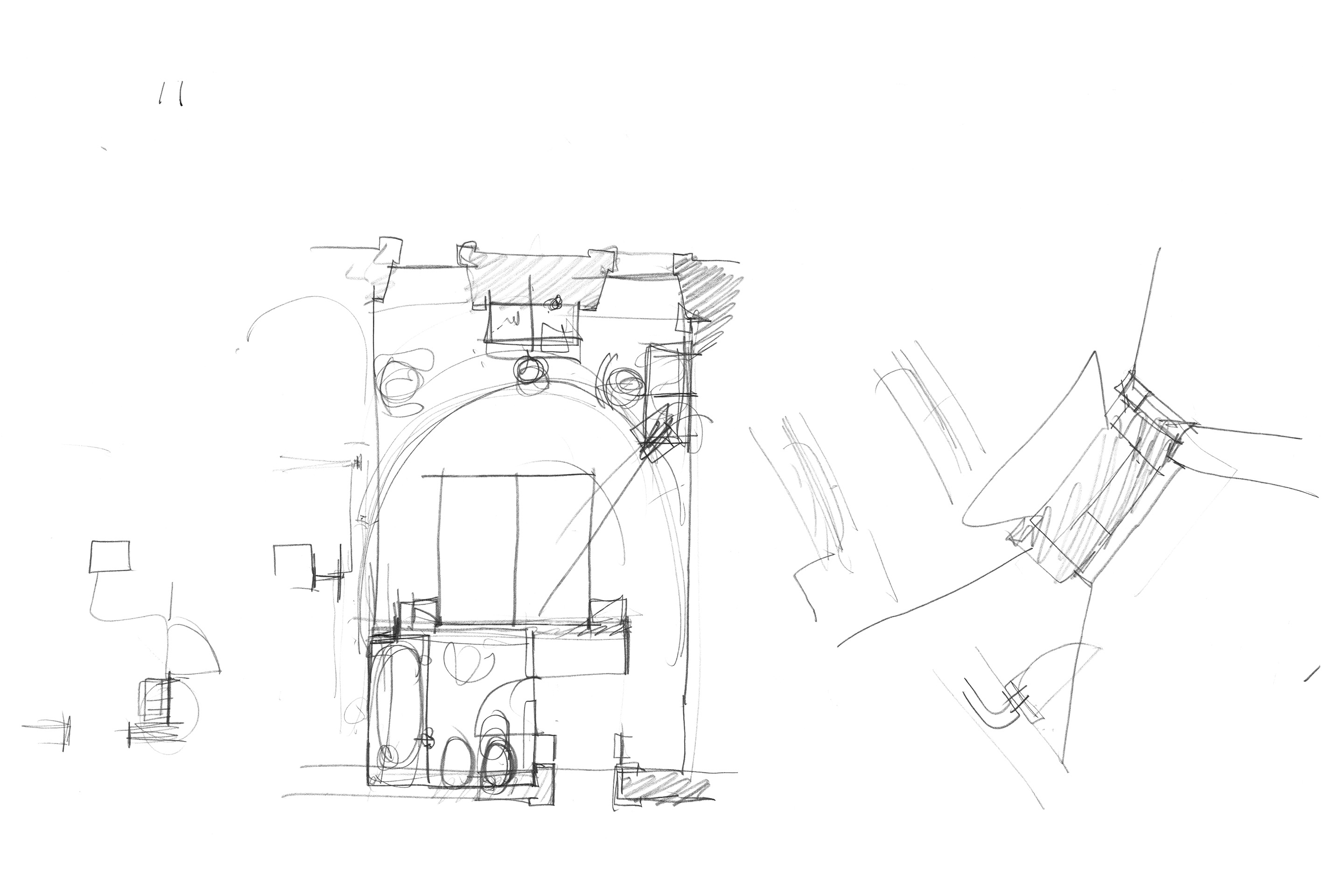

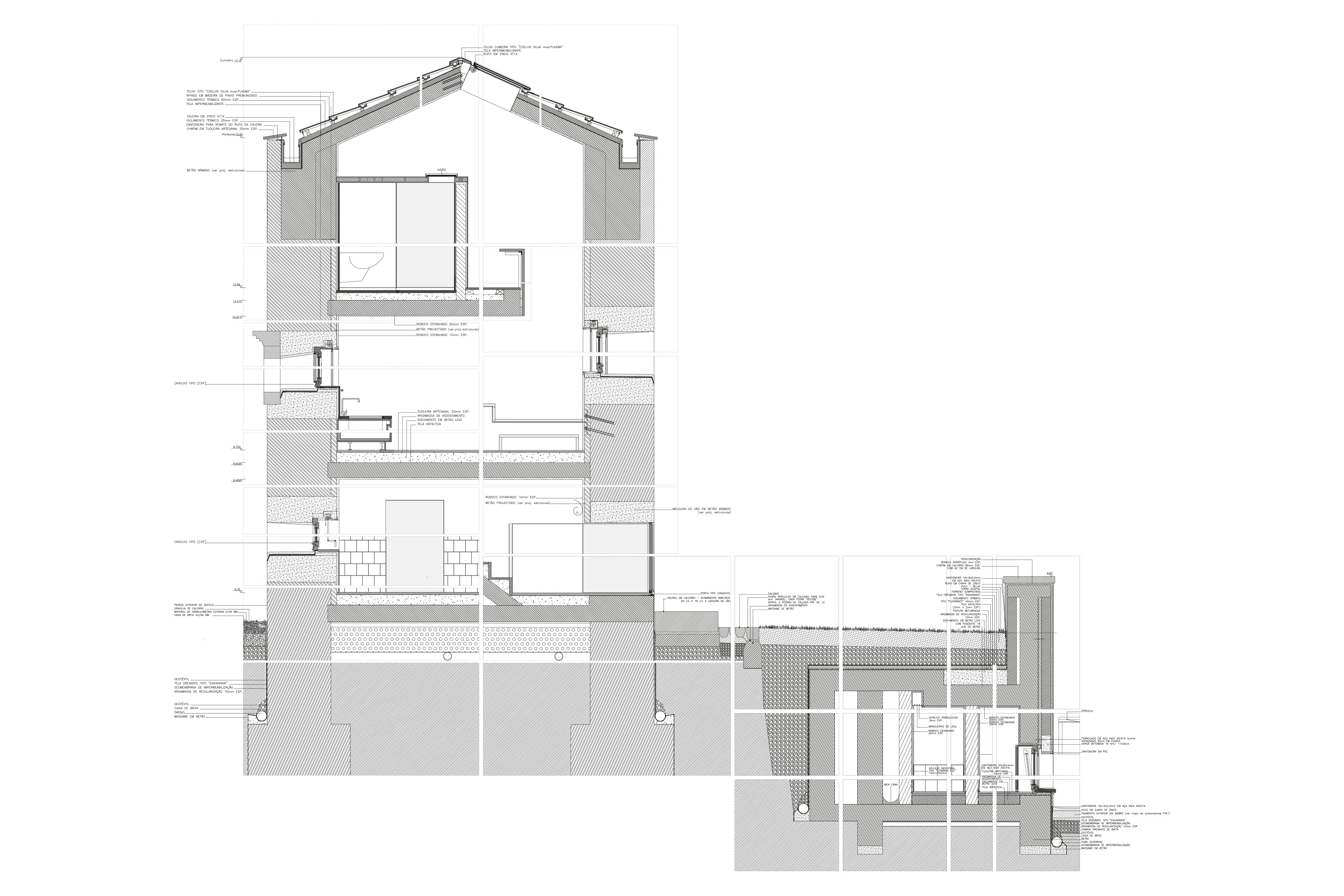

CN: How do you interpret the overall composition and how do you articulate the expression of assembly tectonics in the design of construction details?

ESdM: I can’t write without commas. Without punctuation, there is no time, no rhythm, no pauses, no silences and no separations, only undefined noise remains. I believe that details serve as the punctuation of architecture. There must be a detail to connect a window frame in continuity with a wall, or to separate it. This is the joint and there are two ways of doing architecture, with or without joints. Mine embodies an almost neoplastic vision of architecture. Each material has its own plane that must then relate to the others without conflict, otherwise water will find its way in.

CN: You have carried out numerous interventions on buildings, experimenting with different approaches each time. What are the main reasons that lead you to propose restoring or replacing a building?

ESdM: I think David Chipperfield’s design for the restoration of the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin is remarkable. He was tasked with the assignment and he fully maintained the architecture, materials and all the original details of Mies van der Rohe’s building and provided only the innovations necessary to combat the building’s deterioration keeping them discreet. When a building has architectural value, I believe its identity should be safeguarded; when it does not, it can be replaced. People are often hesitant to admit that we can sometimes create things better than those of the past, instead it is often easier to assume that everything old is valuable, but that is not always true.

CN: When it comes to intervening on the built heritage, the utmost attention must be paid to the interpretation of the existing, be it historical, documentary, design or material. What is your position regarding the cultural and material protection and conservation of your projects and works?

ESdM: I don’t think it’s a problem of mine. If they are good architectures, people will protect them. If they decide to modernize them, I hope that the interventions remain hidden, preserving the original atmosphere while updating the program or construction according to new requirements. I am absorbed in the present and am excited about it. Today in order to work you need a lot of energy, you have to be obsessed and persistent.

CN: As we were talking about before starting this interview, Brasilia is a real surprise, in some respects a daydream. I recently visited it, and in the superquadra the simple quality of each housing unit and the natural quality of the whole, the way in which contemplative open spaces or relationships can so easily belong to architecture, even at that scale, is amazing.

ESdM: When I was in Brasilia, in the superquadra with all those gardens, I realised that the modern was really designed for that reality and not in Sweden or Bauhaus, the residential blocks are raised off the ground, services and equipment are organised in bands, people are happy and feel safe.

CN: One wish you would like to fulfil through architecture?

ESdM: I think challenging gravity is an ambition of all architects. What is Gothic? Liberation from gravity. What do the pilotis represent?