"Knowledge transfer is the key discipline"

Future Cities Laboratory

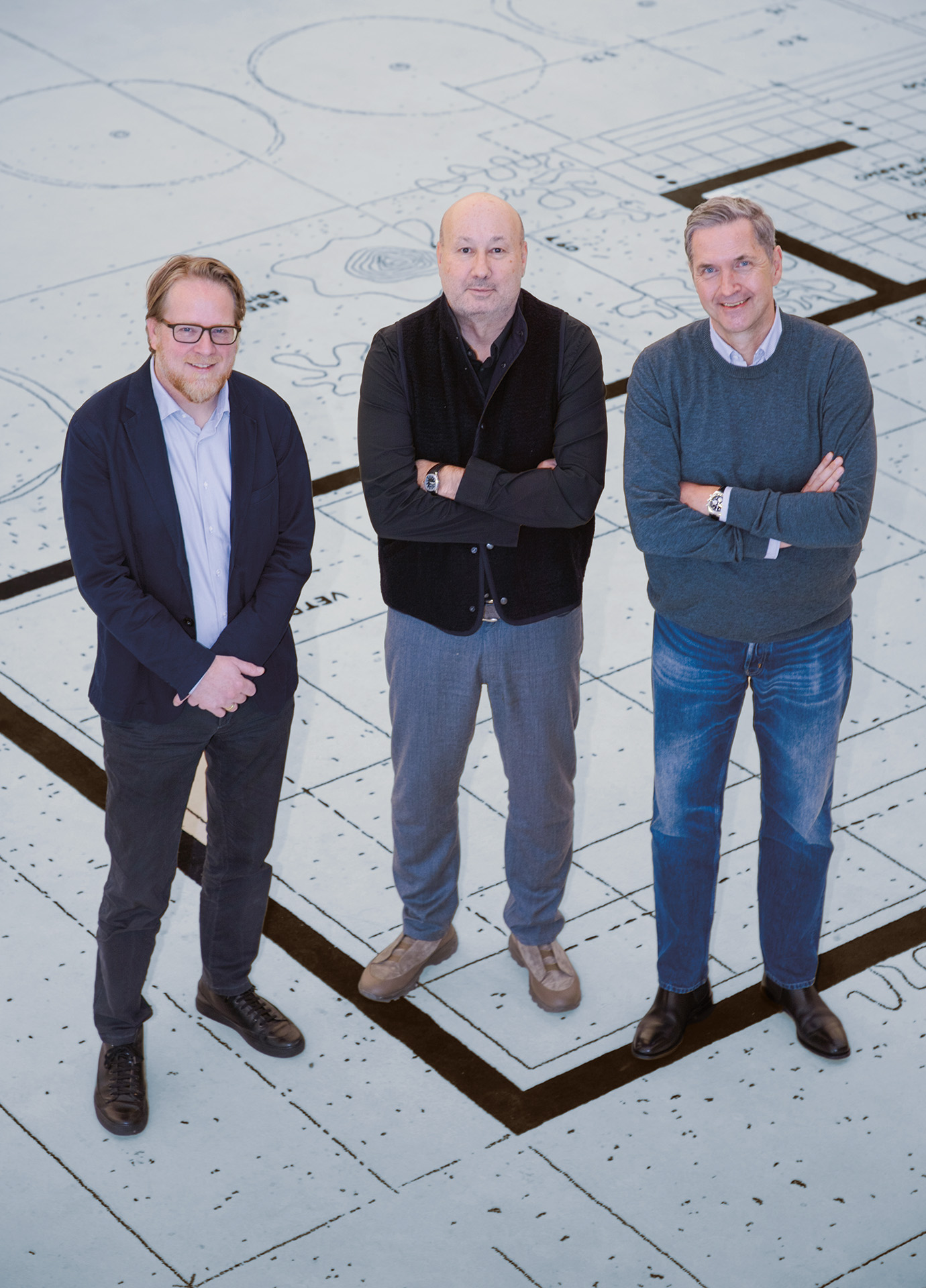

Why does FCL face up to the complexity of urban life? In this interview, the three directors explain what motivates – and challenges – them on a daily basis.

Future Cities Laboratory (FCL) is a collaboration between ETH Zurich and the three universities NUS, NTU, and SUTD in Singapore, which are jointly researching the development of sustainable settlement systems. The transfer into practice is also important: the results should generate direct practical added value in addition to scientific findings. Why this practical relevance?

Sacha Menz: Time is pressing. Global crises – climate change, species extinction, social, economic and political conflicts – are on the rise; we need to make the transition to sustainable development before the tipping point is reached. Theory is of little use if it is not implemented effectively. The FCL modules convey an understanding of complex interrelationships and develop innovative, practical instruments. These include new approaches as well as models and tools for collecting, analysing, and evaluating data, in particular for data-based and scientifically robust forecasting. These enable decision-makers to prioritise and optimally deploy resources in order to promote sustainable and liveable settlement systems.

Why do we need transdisciplinary research teams like those in the FCL modules?

Arno Schlüter: Settlement systems are complex systems, characterised by equally complex issues with a large number of actors, interdependencies, conflicting objectives, as well as contradictory boundary conditions and dynamics. There are no simple answers. However, a comprehensive approach is crucial for sustainable development. Its basis is a holistic, transdisciplinary view of the city that is often unfamiliar to specialised experts and therefore all the more valuable. This is the only way to open up new perspectives.

The Zurich and Singapore locations have different cultural, economic, political, and climatic conditions. The researchers focus on the respective context but also gain overarching insights. How is knowledge transferred into practice?

S.M.: Of our four pillars – science, design, engineering, and governance –, the latter is the key discipline. The transfer of research results to politics and the authorities is challenging. Legislation and standardisation – policymaking – are not the task of science. But we want to support the decision-makers; our concepts and tools can provide them with guidance and practical help. That is why we seek contact with the authorities. In Switzerland, we work with the Directorate of the Federal Office for Spatial Development, but also with cantonal and municipal planning offices. We do not carry out contract research, but some of our projects in Switzerland are conducted in collaboration with the authorities. We maintain an intensive dialogue with the city of Zurich, where ETH Zurich is located. There is a great deal of mutual interest, because there is a lot of valuable knowledge on both sides.

When is the right time to start the dialogue between research and practice?

A.S.: Ideally, the process begins with an exchange on where the specific issues lie locally. Our research is organised into modules with different thematic focuses, but they all work to generate knowledge in order to better understand the interactions. Only with this knowledge can we make meaningful decisions for the sustainable design of our living environment. For example, our students are working with the Zurich administration to investigate how technical innovations, sustainability, and planning processes influence each other. We do not decide whether new processes are implemented, but we can help to initiate them. Another example is digital tools: many modules are developing innovative tools that increasingly use artificial intelligence, such as machine learning. These tools are being tested in practice and should enable government agencies and offices to make pioneering decisions faster and more reliably. As mentioned earlier, the ultimate objective is that our findings are also incorporated into the design of guidelines or standards.

There are also examples of this, particularly in Singapore.

Thomas Schröpfer: In Singapore, decision-making is more reactive than in Switzerland. Some of our findings have already been taken into account in legislation; we are keen to see what effect they have. Conversely, the authorities in Singapore are more involved in our research than in Switzerland, even more so than it would be the case in Germany or the USA. If you are doing research at a university in Singapore, the authorities know exactly what you are doing and contact you with questions. In the initial phase of research programmes, common goals are agreed upon. At the same time, the authorities are proud of FCL: we were invited to organise a specialist event together with the Ministry of National Development, which took place alongside the World Cities Summit, and to present an exhibition on the premises of the most important planning authority, the Urban Redevelopment Authority. Also, in Singapore, there are more and more research departments in the authorities themselves, which work more directly on the practical problems of the authorities than we do at the universities. This is where the distinction is particularly important: we analyse questions that go beyond pure problemsolving. Communicating this to the authorities is not always easy.

Why is it important to insist on academic freedom of research?

T.S.: FCL combines basic and applied research. While authorities work in a practical manner, we focus on long-term, overarching questions. Using specific case studies, we enter the field of applied research, develop innovative methods, analyse urban dynamics, and develop transferable findings that go beyond local challenges and can be applied worldwide.

A.S.: The radical interdisciplinarity of FCL is a strength that is difficult for authorities to achieve because they have to focus on their sectorial targets. This also distinguishes FCL from other research programmes. As one of the few teams in the world, we manage to cover a wide range of topics and still go into depth – also because we have the critical mass to do so. We can look at problems from different perspectives and find synergies. This is unique and necessary: thinking in disciplinary silos leads to conflicts of objectives.

Is there also a transfer of knowledge across continents?

S.M.: We have succeeded in encouraging planning authorities from Switzerland and Singapore to exchange ideas. We also bring together participants from all over the world at our annual summer school courses and workshops.

T.S.: One potential knowledge transfer concerns how to deal with urban heat islands, which we are researching in the Cooling Singapore project. Cooling the city has always been a problem in Singapore. Swiss cities are now also increasingly confronted with rising temperatures and extreme precipitation; issues such as sponge cities, well-being in outdoor spaces, and biodiversity are becoming more important.

To what extent can findings from Singapore be transferred to Zurich – and vice versa?

A.S.: Conversely, Swiss cities, which are many centuries old, are characterised by great typological diversity. This offers new perspectives. Due to the need to adapt our buildings to the cold climate, Switzerland is in a different situation in terms of materials and building technology. The experience gained in this context can also be helpful for the tropical climate.

And what are the goals for the future?

A.S.: In the next programme, we will extend the range. Zurich and Singapore are comparable, but they have completely different types of settlements and climate zones. We have already addressed these to some extent, but to what extent can we scale up our work and apply our findings to, say, Amsterdam, London, Toronto, Buenos Aires, or Mumbai?

T.S.: We call it global sandboxing: We want to learn which findings can be transferred and how. Can digital tools developed in a certain context also be used elsewhere? Do they work in places where there is little data? On the other hand, we can now process much larger amounts of data than in the past.

S.M.: What remains is the driving force behind the FCL research programme: people. People are at the centre – their well-being and the sustainability of their habitat.